[NOTE: This article serves as Part III of a 3-part series on Israel’s sojourn in Egypt. The first two parts, published in the February/March 2025, examined the biblical text, archaeology, and historical context in establishing the case for the Israelite sojourn. The critical debate regarding the duration of Israel’s sojourn centers around whether the 430-year period mentioned in Scripture began entirely in Egypt(long sojourn theory) or included 215 years in Canaan before Jacob’s arrival in Egypt(short sojourn theory).

In this continuation, the focus narrows to the beginning of the 215-year short sojourn timeframe—specifically, Joseph’s life and experiences in Egypt from his enslavement to Jacob’s arrival. By analyzing key biblical texts and Egyptian chronology, this study aims to clarify how these timelines intersect and demonstrate how Scripture aligns with historical realities.]

A BRIEF REVIEW OF THE SHORT AND LONG SOJOURN THEORIES

The duration of the Israelites’ sojourn in Egypt has been a subject of considerable scholarly debate. The discussion centers, not on the total period of 430 years, but rather on when this period beganand where it was spent. Two primary views exist regarding the chronology of Israel’s time in Egypt:

- The Long Sojourn Theory – This view holds that the entire 430-year period was spent in Egypt, beginning with Jacob’s arrival and ending with the Exodus.

- The Short Sojourn Theory – This position contends that only 215 years of the 430-year period were spent in Egypt, while the first 215 years occurred in Canaan, beginning with Abraham’s divine covenant.

To breakdown the Short Sojourn chronologically:

- Abram was 75 years old when he received the divine covenant (Galatians 3:17).

- 25 years later, Isaac was born.

- 60 years after that, Jacob was born (Genesis 25:26).

- At 130 years old, Jacob entered Egypt (Genesis 47:9).

When these figures are summed—25 + 60 + 130—they amount to 215 years, marking the period from Abraham’s covenant to Jacob’s arrival in Egypt. The remaining 215 years of the 430-year total were then be spent in Egypt, before the Exodus. As discussed in Parts I and II of this series, the short sojourn aligns more precisely with the textual, historical, and contextual data provided in both biblical records and Egyptian chronology.

Joseph in Egypt: 12th Dynasty or 15th Dynasty (Hyksos)?

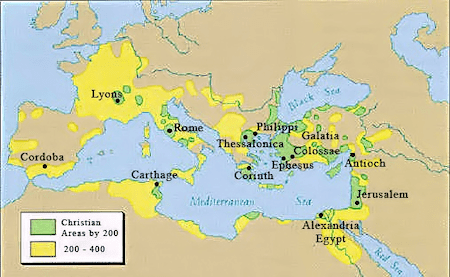

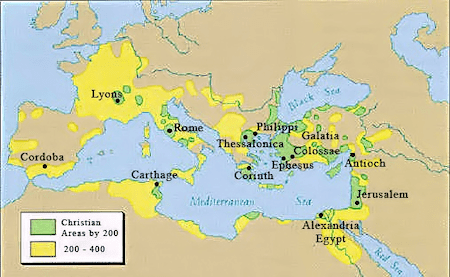

Long sojourn advocates place Joseph’s arrival in Egypt in the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (ca. 1878-1843 B.C.), based on the assumption that the entire 430-year sojourn was spent in Egypt. According to this theory, Joseph arrived at a time when an Egyptian pharaoh held the throne. This approach introduces significant textual and historical challenges. However, a short sojourn timeline places Joseph in Egypt during the 15th Dynasty (ca. 1650-1549 B.C.) and the reign of non-Egyptian rulers known as the Hyksos. Placing Joseph’s rise to power during the Hyksos period aligns biblical history with Egyptian chronology in a way that is both coherent and historically viable.

THE HYKSOS

The Hyksos were a Semitic population[1] that migrated from Canaan into northern Egypt’s Delta, eventually establishing themselves as a ruling class. The term Hyksos is an Egyptian term, which translates to “rulers of foreign lands.” The word Hyksos first appeared as early as the mid-19th century B.C.—roughly 200 years before they assumed rulership. A notable early depiction of Semitic people in Egypt is found in the tomb painting of Khnumhotep II, also known as the Beni Hasan painting. This artwork portrays an entourage of men and women in brightly colored garments. In addition to multicolored garments, the Hyksos were noted for their shepherding lifestyle.

Contrary to early assumptions, archaeologists now agree that the Hyksos were not foreign invaders, but rather Canaanitepeoples who had already been integrated into Egypt through trade, migration, and settlement. Danielle Candelora has argued that the Hyksos rise to power was not the result of a violent invasion but rather a gradual process in which Semitic elites gained influence as Egypt’s centralized authority weakened.[2] Instead of overthrowing Egyptian rule in a sudden conquest, the Hyksos assumed power through a combination of political maneuvering, economic influence, and local governance.[3] As they consolidated control, they adopted Egyptian royal titles and integrated themselves into the existing administrative framework, eventually establishing their own dynasty. This perspective challenges the traditional view of the Hyksos as foreign oppressors and, instead, portrays them as diplomatic rulers who contributed to Egypt’s cultural and technological development.

Ancient historians Josephus, Africanus, and Eusebius differ widely when it comes to the number of years of Hyksos rule. Josephus has 511 years, Africanus 284, and Eusebius 250.[4] The most plausible figure comes from the Turin Canon which records 108 years, giving the six Greater Hyksos kings an average reign of 18 years. Redford points out that there are approximately 32 names of Hyksos kings in the Turin Canon.[5] Most are west Asiatic names, garbled in many cases beyond recognition in the course of transmission. They have defied interpretation for many years, but over time, the total has been reduced to six Great Hyksos in agreement with the historical tradition. The accepted dynastic sequence of the Greater Hyksos is as follows:

- Maibre Sheshi (Egyptianized version of Salatis, also spelled Salitus or Salitis)

- Merwoerre Yaqobher

- Seweserenve Khyan

- Yannass

- Apophis

- Khamudy[6]

The Hyksos, like other regional rulers of fragmented Egypt, initially controlled only portions of the land rather than the entire kingdom. They established dominance over the eastern Nile Delta, assimilating Egyptian royal customs while expanding their authority over surrounding regions. Around 1648 B.C., Salitis (Salatis), the founder of the 15th Dynasty, consolidated power over Lower Egypt, ruling from Memphis to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Hyksos era marked a period of political decentralization, with Egypt effectively divided in two: while Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta, including the biblical land of Goshen) was ruled by the Hyksos kings, Upper Egypt (southern Egypt) remained under the control of native Egyptian pharaohs. Although Thebes remained under native Egyptian control, it functioned as a vassal state, paying tribute to the Hyksos. This relationship is documented in the Kamose stela, where Kamose (17th Dynasty) laments that no one can settle down due to being “despoiled by the imposts of the Asiatics,” underscoring the heavy tributes exacted by the Hyksos rulers.[7]

Despite this fragmentation, Egypt flourished culturally, militarily, and commercially, benefitting from Hyksos innovations, including advancements in bronze weaponry, horse-drawn chariots, and fortified architecture. Archaeologists now recognize that many native Egyptians even collaborated with the Hyksos rulers, allowing garrisons to be stationed in their towns in Upper Egypt.[8]This cooperation extended to high-ranking Egyptian officials who served under the Hyksos administration. It is possible that the Hyksos used these native mentors to counsel them.

The Hyksos were not forceful in compelling the Egyptians to accept their laws, religion, or culture. The reverse might be nearer to the truth. Hyksos rulers integrated Egyptian administrative and legal practices, including dating events by regnal years, as seen in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, which was copied in the 33rd regnal year of Apophis.[9] The frequent use of the Egyptian title “treasurer” by Hyksos officials further suggests that their government closely mirrored Egyptian bureaucracy. Notably, scarab seals belonging to treasurers of the Hyksos dynasty suggest that this office held significant influence within the Hyksos bureaucracy. However, their reliance on local vassals—both Asiatic and Egyptian—to govern regions reflects a distinctly Near Eastern tradition, demonstrating a fusion of Egyptian and Semitic governance styles.

Although the Hyksos assimilated many aspects of Egyptian religious practices, they also integrated their own belief systems, resulting in a unique fusion of traditions.[10] The Semitic inhabitants of Avaris retained elements of their Levantine heritage and culture,[11] though over time they became heavily Egyptianized.[12] This distinctive cultural blend gradually spread to other cities, leading to an increase in the Hyksos presence, as more settlers from southern Canaan became part of this growing community.[13]

The Hyksos were not the Israelites, despite some historical attempts to equate the two. While Joseph and the Hyksos kingdom do overlap chronologically, their identities remain distinct. The connection between the Israelites and the Hyksos is largely derived from the third-century B.C. historian Manetho, who associated the Hyksos with the Hebrews. However, his account, preserved only in Josephus, is heavily influenced by an anti-Semitic Egyptian perspective.

Manetho’s first Hyksos ruler, Salatis, has been linguistically linked by some scholars to the biblical Joseph. This connection stems from the phonetic similarity between the Greek rendering Salitis and the Hebrew titleShalit (שָׁלִיט, shālit), meaning “governor” or “ruler”—the very title given to Joseph in Genesis 42:6: “Now Joseph was the governor over the land.” While this correlation is intriguing and does contextually link Joseph to the Hyksos period, it has not—and likely cannot—be proven archaeologically. Nonetheless, Manetho and Josephus wrote in Greek, a language that often appends the -is suffix to masculine names. This practice is evident in the case of Apophis, a Hyksos ruler whose name derives from the original Egyptian Apep or Apepi. If a similar Greek modification was applied to Salitis, then the core of his name may have been Salit. Given that the Hyksos were foreign rulers in Egypt, and that Joseph himself was a Semitic outsider elevated to a position of power, the possibility that his influence contributed to or coincided with the Hyksos period is a topic worth deeper exploration.

By the 17th century B.C., Egyptians had developed a strong resentment toward the Hyksos, a sentiment that extended toward all Semitic peoples living in Egypt. The native Egyptian rulers of Thebes in Upper Egypt, dissatisfied with their vassal status under the Hyksos, eventually launched a rebellion that would escalate into full-scale war. As part of their propaganda efforts, these Theban pharaohs vilified the Hyksos, portraying them as oppressive foreign rulers who had unjustly seized Egyptian land. This narrative persisted through later Egyptian history, including the period of Greek rule, shaping Egypt’s enduring hostility toward the Hyksos. As a result, after the Hyksos had been expelled, Egyptians destroyed most goods and records associated with the Hyksos. Thus, it is not surprising that our knowledge of the administration is limited.

AVARIS (TELL EL-DAB’A): THE HYKSOS CAPITAL

Archaeological Evidence

The Hyksos made their capital at Avaris (Tell el-Dab’a), which is in the exact geographical region of the biblical land of Goshen. Remarkably, archaeological discoveries confirm that Avaris was home to the largest known settlement of Asiatic (Semitic) peoples in Egypt.

Historical and archaeological evidence indicates that the population under Hyksos rule in ancient Egypt was notably multi-ethnic, comprising individuals of local Egyptian descent, descendants of Levantine settlers, offspring from mixed unions between Egyptians and Levantines, as well as newcomers from the Levant and other regions of the Eastern Mediterranean.[14] The presence of various ethnic groups and the integration of foreigners into significant roles during the Hyksos period provide a plausible historical context for Joseph’s story, illustrating how a foreigner could achieve substantial authority in a multicultural Egyptian society.

Manfred Bietak assigns the tombs and statuary at Tell el-Dab’a to the 12th Dynasty, specifically during the reign of Senusret III. His excavations reveal a planned Egyptian settlement at site F/I, established in the early 12th Dynasty (Phase N), which was later expanded by Senusret III, who constructed a memorial temple for Amenemhat I at ‘Ezbet Rushdi (Phase M-K). During the late 12th Dynasty, a Canaanite community settled in the location, as evidenced by the presence of distinctive Asiatic architectural styles, including middle-room, broad-room, and hearth-house designs, as well as a cemetery of weapon-bearers and high dignitaries.[15]

One of the most significant discoveries at this site is a larger-than-life statue of a high-ranking prince, found within a chapel atop a grand tomb (Phase H). Another high-quality statue of a Western Asiatic dignitary, featuring the distinctive mushroom-shaped coiffure, originates from Phase G/4 and is now housed in the Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich. These figures represent prominent Asiatic officials who had attained high status within Egyptian society during the late 12th and early 13th Dynasties.

A particularly notable find includes a scarab bearing the title “Ruler of Retjenu,” which was an Egyptian designation for the highest authority over Canaan and its surrounding territories. This title was likely conferred upon the most influential member of the Asiatic community residing in Avaris, suggesting that this tomb belonged to a leading Canaanite official.[16]

Cusae, 40 kilometers south of Hermopolis, was an additional administrative center for the Hyksos. From this point they regulated river traffic, imposing taxes on ships from Upper Egypt crossing that line. Between 1670 and 1650 B.C., the river was still open, but shortly thereafter, Cusae marked the boundary north of which taxes to the ruler of Avaris had to be paid.[17]

Avaris, Goshen, and Rameses: Converging Archeological and Biblical Evidence

The biblical narrative and archaeological evidence converge in a compelling way at Avaris, the heart of the Land of Goshen. Joseph informed his family that they would settle in Goshen: “You shall dwell in the land of Goshen, and you shall be near me, you and your children and your children’s children, and your flocks, your herds, and all that you have” (Genesis 45:10) As part of the Nile Delta, Goshen was fertile and suitable for agriculture and grazing, which would have been important for the livelihood of Joseph’s family. In the biblical narrative, Avaris was known as Rameses. According to Scripture, Jacob and his sons settledin the Land of Rameses (Genesis 47:11).

Since the region of Goshen was already referred to as Rameses centuries before Rameses the Great of the 19th Dynasty was born, it is possible that the name was either associated with an earlier ruler during Jacob’s time or, more plausibly, was an editorial update by an inspired biblical writer. The latter scenario is a likely explanation as place names were often updated in ancient texts to reflect later geographical or political realities, ensuring clarity for subsequent audiences.

While the accounts detailing Moses’ birth (Exodus 2:1-11) and his interactions with Pharaoh (Exodus 5-12) do not specify an exact location, the narrative context suggests a royal capital situated along a branch of the Nile (Exodus 1:15-2:10; 5-12). The description of Pharaoh’s decrees, Moses’ placement in the river, and the presence of Egyptian court officials aligns with a major administrative and residential center. Furthermore, the geographical features referenced in the text, including its proximity to the Nile(Exodus 1:22; 2:3-6; 7:14-8:12) and accessibility to the Sinai region via overland routes (2:15; 4:18-28), strongly correspond to the known location and characteristics of Avaris/Rameses. Moreover, the name Rameses is specifically referenced in Exodus 1:11, indicating that the Israelites labored in the construction of storage cities Pithom and Rameses, and Rameses is also mentioned in describing the Israelites’ departure from Egypt and theonset of the Exodus (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:3,5).

In addition to being the key place of settlement for the Israelites from the time of Joseph through Moses, the Goshen region and Avaris may have been the setting for Abraham’s sojourn in Egypt. Though the biblical text does not explicitly state where Abraham encountered Pharaoh, the 12th Dynasty settlement of a large population of Canaanite peoples in Avaris coincides with the timing of Abraham’s arrival, ca. 1875 B.C.[18] It is possible that Abraham spent time in this area among these settlers, some of whom may also have fled the famine in Canaan (Genesis 12:10). When Abraham visited the region, it was called “Hutwaret,” meaning “House of the Region” or “Estate of the District.” Though 12th dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat I established the city, the royal court primarily resided in the capital, Itjtawy, near the Faiyum region. The strategic importance of this city suggests that subsequent pharaohs, such as Senusret III and Amenemhat III, may have maintained administrative or military presences there to oversee trade routes and border security.

Long sojourn advocates place Joseph in Avaris during the 12th Dynasty due to the large Canaanite population and evidence of Asiatic dignitaries. Some have even theorized that the tombs and statues of Asiatic officials represent Joseph. Yet, the 12th Dynasty dignitaries were officials serving under native Egyptian rulers.

Dating Joseph to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom is also problematic because, for example, the sale of Joseph for 20 shekels of silver (Genesis 37:28) fits squarely within the documented slave prices of the 18th to 17th centuries B.C., a period that overlaps with the early Second Intermediate Period in Egyptian history. Archaeological records from sites such as Mari and Alalakh confirm that 20 shekels was the standard rate for slaves during this time. In contrast, earlier periods such as the Middle Kingdom reflect lower averages, typically around 10 shekels. As Egyptologist Kenneth A. Kitchen explains, prices began to rise after this point, eventually reaching 30 shekels or more in later centuries.[19] Joseph’s sale price, therefore, aligns well with a date around 1660 B.C., consistent with the Hyksos era in Egypt and more historically credible than a Middle Kingdom setting in the early 12th Dynasty.

Consider also that during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055-1650 B.C.), trade with Canaan was primarily maritime, concentrated through coastal ports like Byblos, which became so pivotal in papyrus exchange that the Greek word biblion (“book”) derives from its name. However, by the mid-17th century B.C., as the Middle Kingdom declined and the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1550 B.C.) began, these trade patterns shifted significantly. According to Dr. Daphna Ben-Tor of the Israel Museum, maritime contact with Byblos ceased during this transitional era and overland trade routes between Canaan and the eastern Nile Delta became the dominant commercial network. This change aligns closely with the account in Genesis 37, where Joseph is sold at Dothan to an Ishmaelite caravan coming from Gilead. By ca. 1650 B.C., a likely date for Joseph’s entry into Egypt under a short-sojourn model, such caravans were common along inland trade arteries connecting Canaan to the Hyksos-held Delta. Dothan’s proximity to these routes enhances the plausibility of the narrative, supporting the view that Joseph’s rise occurred during the early Hyksos period rather than the centralized Middle Kingdom.[20]

Joseph’s rise to power in Egypt aligns more naturally with the political and cultural context of the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1550 B.C.) than with the earlier Middle Kingdom. During this time, Semitic-speaking Hyksos rulers dominated the Nile Delta, ruling from Avaris, a region later identified in Genesis as the land of Goshen (Genesis 47:11). The biblical narrative presents Joseph, a Semitic foreigner, rapidly ascending to high administrative office (41:40-44), marrying into a priestly class (41:45), and settling his family in the most fertile part of the Delta—developments that are far more plausible under Hyksos rule, which was notably open to Asiatic influence. Additionally, the mention of chariots (41:43) and Ishmaelite trade caravans from Gilead passing through Dothan (37:25) matches known Second Intermediate Period conditions, when overland trade with Canaan had largely supplanted maritime routes. Taken together, these details form a coherent picture that places Joseph’s rise during the early Hyksos period, not the centralized and ethnically exclusive Middle Kingdom.

JOSEPH IN EGYPT: ALIGNING THE BIBLICAL AND EGYPTIAN CONTEXTS

Joseph’s Enslavement in Egypt

The detailed biblical account of Joseph’s time in Egypt can further clarify the alignment of the short sojourn with Egyptian chronology. According to the Genesis account, Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery in Egypt (Genesis 37:28). Evidence of a slave trade from Canaan to Egypt is, therefore, a crucial aspect of converging the biblical and Egyptian records. During the time that the Hyksos consolidated control over Egypt, around 1650 B.C., Egypt had an active Semitic slave trade, as evidenced by records of the founding families of the Hyksos dynasty.[21]

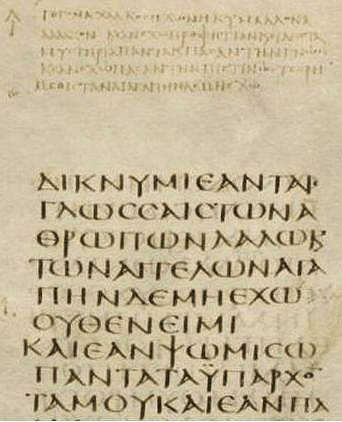

One of the most significant archaeological findings identifying Semitic slaves in Egypt during the Hyksos period is the Brooklyn Papyrus.[22] Dated to the 13th Dynasty (Middle Kingdom, ca. 1809-1743 B.C., slightly before the Hyksos period), this document lists the names of household servants and slaves in Egypt, many of whom bear Semitic names, indicating they were of Canaanite or Asiatic origin. The text contains a record of approximately 95 individuals, with at least 30-40% of the names being Semitic, demonstrating a significant presence of Semitic-speaking individuals in servitude. The names suggest that these individuals were likely captives or indentured laborers, providing strong evidence for a well-established practice of enslaving Asiatic peoples in Egypt.[23] This aligns with the biblical narrative of the Israelites’ eventual enslavement, reinforcing the plausibility of their presence in Egypt prior to and during the Hyksos period.

Joseph’s Rise in the House of Potiphar

In the story of Joseph, Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh and captain of the guard, bought Joseph from the Ishmaelites (Genesis 39:1). Joseph’s enslavement and rise within the house of Potiphar presents an intriguing case within the ethnic and political landscape of Hyksos-era Egypt. The Genesis account explicitly emphasizes Potiphar’s Egyptian identity, distinguishing him from the ruling Semitic Hyksos elite. This is seen in several passages:

- Genesis 39:1—“Now Joseph had been brought down to Egypt, and Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, the captain of the guard, an Egyptian, had bought him from the Ishmaelites who had brought him down there.”[24]

- Genesis 39:2-3—“The Lord was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptianmaster. His master saw that the Lord was with him and that the Lord caused all that he did to succeed in his hands.”

- Genesis 39:5—“From the time that he made him overseer in his house and over all that he had, the Lord blessed the Egyptian’s house for Joseph’s sake.”

The repeated emphasis on Potiphar’s Egyptian identity suggests that this was significant to the Genesis writer’s overall narrative. This emphasis would not be necessary in an administration led by native Egyptians in which case the Egyptian ethnicity of the leaders would be a given trait. Interestingly, the pharaoh whom Joseph later served is never explicitly called an Egyptian, which strengthens the argument that he may have been a Hyksos king rather than a native Egyptian Pharaoh.

As captain of Pharaoh’s guard, Potiphar likely held a high-ranking military position, one of the few elite roles still available to native Egyptians under Hyksos rule. The Hyksos had adopted aspects of Egyptian administration,[25] and native Egyptians still played key roles in governance and military service, albeit under Semitic rulers. For Potiphar, owning a capable and talented Semitic slave could have been advantageous, particularly in navigating the social hierarchy under Hyksos rule. Scholarly evidence supports the argument that native Egyptians worked alongside or under Hyksos leadership during the 15th Dynasty. Officials with distinctly Egyptian names served as treasurers under the Hyksos rulers, though whether these individuals were ethnically Egyptian or descended from foreign lineages identifying as Egyptian over generations remains uncertain.[26] Additionally, the Carnarvon Tablet—an inscription also known from stela of the Theban 17th Dynasty king Kamose—mentions an Egyptian official named Teti, son of Pepi, who angered Kamose by allowing the Egyptian town Neferusi to become heavily populated by Asiatics. This suggests Teti was subordinate to Hyksos authority.[27]

Joseph’s rise to overseer of the household (Genesis 39:2-5) reflects his trustworthiness and administrative skill but also suggests that Potiphar saw no immediate ethnic or political threat in him. The Hyksos era would have been more favorable than a native Egyptian dynasty for a Semitic foreigner to gain status and influence. However, Potiphar’s status as an Egyptian under a Semitic regime would have added a layer of complexity to Joseph’s rapid rise since native Egyptians would have operated in subordinate or limited roles within a Hyksos government, possibly leading to tensions between them and their Semitic rulers. Thus, Joseph’s ethnic identity, though advantageous under Hyksos rule, may have also contributed to jealousy, suspicion, and his ultimate imprisonment.

Joseph’s Imprisonment: A Reflection of Ethnic and Social Tensions?

Despite Joseph’s success, the false accusation by Potiphar’s wife and subsequent imprisonment (Genesis 39:19-20) raises questions about the social dynamics of the time. Given the racial and political complexity of the era, several factors may have played a role in Joseph’s sudden fall from favor:

- Resentment in Potiphar’s Household: While Potiphar may have seen Joseph’s abilities as beneficial, his elevation above other native Egyptians within the household could have caused internal resentment. His position of authority may have been viewed as inappropriate or even undesirable within an Egyptian social structure, especially if ethnic biases were present.

- Egyptian Prejudices: Though Joseph rose to prominence in the house of Potiphar, tensions must have existed due to the deep-seated prejudices held by native Egyptians. The Egyptian perception of Semitic peoples as “dogs” is well attested in historical sources and aligns with broader Egyptian attitudes toward foreigners. In the Tale of Sinuhe, the Asiatic rulers are explicitly compared to dogs, a metaphor that, while potentially implying loyalty, carries predominantly negative connotations in the Near Eastern cultural context.[28] The dog metaphor in Egyptian thought often symbolized uncleanliness, servitude, or lesser status, making its application to Asiatic rulers particularly revealing. This linguistic and literary usage reflects the longstanding Egyptian view of Semitic peoples as inferior or undesirable, reinforcing the historical tensions between Egypt and its northeastern neighbors.

In The Prophecy of Neferti, the Asiatic peoples are portrayed as uncivilized nomads, contrasting sharply with the Egyptians, who are depicted as settled and orderly city-dwellers. The text describes the ‘Aamu (a term used for Asiatics) as a disruptive force, stating: “The ‘Aamu travel in their strength, frightening the hearts of those who are harvesting and taking away the yoked oxen at the plough.”[29] This passage underscores the Egyptian perception of Asiatics as chaotic and destabilizing forces within society.[30]

These passages underscore the ethnic tensions that would have influenced Joseph’s experience in Egypt. Though he achieved high status, his Hebrew identity may have still set him apart in certain social contexts, making his rise to power all the more remarkable within a society where Egyptians sought to maintain clear distinctions between themselves and foreign Semitic groups. - Potiphar’s Wife and Social Perception: The accusation from Potiphar’s wife is significant within this context. If Joseph, a Semitic slave, had been accused of attacking an Egyptian noblewoman, it would have been highly scandalous, particularly given the underlying ethnic divisions of the time. Genesis 39:14-15 records her accusation: “She called to the men of her household and said to them, “See, he has brought among us a Hebrew to laugh at us. He came in to lie with me, and I cried out with a loud voice.” The phrase “brought among us a Hebrew” suggests a racial or ethnic undertone, implying that Joseph’s foreign status made him an easy scapegoat. His Semitic identity may have worked in his favor for advancement in Potiphar’s household, but in this moment, it made him more vulnerable to accusation and punishment.

- Potiphar’s Response: An Unusual Leniency? Given the severity of the charge, the expected punishment for such an offense against an Egyptian noblewoman would have been immediate execution.[31] Instead, Joseph was imprisoned (Genesis 39:20). Some scholars suggest that Potiphar may have doubted his wife’s account but was forced to act due to social pressures. Alternatively, his decision to imprison rather than execute Joseph may indicate that he still valued Joseph’s abilities or wished to avoid unnecessary conflict within a Hyksos-dominated Egypt.

Joseph’s Shaving Before Pharaoh: An Unconvincing Argument Against the Short Sojourn

Genesis 41:14 (ESV): “Then Pharaoh sent and called Joseph, and they quickly brought him out of the pit. And when he had shaved himself and changed his clothes, he came in before Pharaoh.”

One argument often presented against placing Joseph in the Second Intermediate Period under a Hyksos ruler is the claim that his act of shaving before meeting Pharaoh suggests he served a native Egyptian king rather than a Hyksos ruler. This reasoning assumes that because later Egyptian propaganda often depicted the Hyksos with beards to emphasize their foreign nature, a Hyksos king would have also required his officials to maintain beards. However, this argument rests on a misunderstanding of both Egyptian artistic conventions and broader cultural norms, failing to consider the full historical and archaeological context.

The assumption that all Hyksos rulers were bearded is based largely on Egyptian depictions of foreigners, which often exaggerated certain features to distinguish them from native Egyptians. The Hyksos ruled over native Egyptians and sought to legitimize their authority by adopting Egyptian customs, including regnal dating systems and courtly traditions. There is no historical evidence from the Hyksos period to indicate that they enforced a strict policy regarding facial hair among their officials, nor that they themselves universally wore beards. Egyptian artistic representations of foreigners were often symbolic rather than literal.

Additionally, personal grooming held significant cultural importance in Egyptian society, especially within royal and religious contexts. Egyptian officials were typically clean-shaven, and beards—when worn by Egyptians—were often artificial and reserved for royalty or deity figures rather than an everyday personal choice. It was standard practice for anyone appearing before a ruler to be well-groomed, regardless of whether the king was Egyptian or Hyksos.

The claim that Joseph’s shaving contradicts his service under a Hyksos king lacks historical and cultural support. The act of shaving was a common Egyptian courtly practice, not an indication of the ruler’s ethnicity. The Hyksos blended Egyptian and foreign customs in governance, and there is no evidence to suggest they imposed a strict requirement for beards among their officials. Thus, Joseph, who had likely been imprisoned for at least two years (Genesis 41:1), would have naturally needed to clean himself, shave, and change his clothes before standing before Pharaoh. Rather than disproving the short sojourn model, Joseph’s story aligns well with the political and cultural context of the Hyksos period, reinforcing the plausibility of his rise to power under their rule.

Pharaoh Acknowledging a Foreign God: A Strong Argument for a Hyksos Ruler

Genesis 41:38-40 records an extraordinary statement by Pharaoh: “Can we find a man like this, in whom is the Spirit of God?” Then Pharaoh said to Joseph, “Since God has shown you all this, there is none so discerning and wise as you are. You shall be over my house, and all my people shall order themselves as you command. Only as regards the throne will I be greater than you.” Such a declaration is unprecedented in Egyptian history. In native Egyptian theology, the pharaoh was the embodiment of divine authority, the living son of the gods, acting as the bridge between the deities and his people. The Egyptian priesthood and economy were wholly intertwined with this religious system. For a native Egyptian ruler to openly elevate the God of a foreign slave above Egypt’s deities would have been an unthinkable act—an outright betrayal of his own legitimacy and a direct challenge to the priestly caste that upheld pharaonic rule. This alone strongly suggests that the Pharaoh in question was not a native Egyptian but rather a Hyksos ruler.

Yet, even if a Hyksos ruler did not recognize Yahwehby name—since God had not yet revealed this to Moses (Exodus 3:14-15)—the text of Genesis uses the name Elohim, the very name of the Creator in Genesis 1. This would have been a completely foreign concept in an Egyptian setting. The Egyptian pantheon was highly structured with supreme gods like Ra, Amun, and Ptah—none of whom could be linguistically or theologically equated with Elohim. The fact that Pharaoh acknowledges the God of Joseph as the only deity capable of interpreting dreams (Genesis 41:8)undermines the entire Egyptian religious system.

A Hyksos pharaoh, however, would have had political motivation to use Joseph’s interpretation to denigrate the native Egyptian gods. By elevating Elohim over Egyptian deities, a Hyksos king could have subtly reinforced his rule by undermining Egyptian religious traditions and legitimizing Semitic religious influences within the royal court.

Moreover, Pharaoh’s declaration that “the Spirit of God” dwelt in Joseph is entirely alien to native Egyptian religious thought. Egyptian theology did not attribute divine inspiration to mere men—only the pharaoh himself was considered the direct intermediary of the gods. The idea that a foreign servant could be filled with the spirit of a god would have been entirely incompatible with Egyptian religious beliefs, further supporting the argument that this pharaoh was not Egyptian but a Semitic Hyksos ruler.

Even the linguistic evidence supports this interpretation. The term for God used in the passage is El, a common Semitic word for “god” found throughout Canaanite and Near Eastern cultures but never associated with any deity in the vast Egyptian pantheon. Egyptologists who dismiss the Joseph narrative as fiction do so because they cannot reconcile this language with native Egyptian beliefs. However, if the Pharaoh in the text was a Hyksos king, then these cultural and religious anomalies align perfectly.

Thus, rather than being an argument against the historicity of the Joseph account, Pharaoh’s extraordinary words actually provide strong confirmation that Joseph served under a Hyksos ruler during the 15th Dynasty. The alignment of this narrative with historical and cultural realities makes it far more plausible than the claim that an Egyptian Pharaoh would have uttered such a statement.

Joseph’s Rise to Power: Over All Egypt?

The biblical account in Genesis 41:41-43 states that Pharaoh placed Joseph in authority over “all the land of Egypt”:

And Pharaoh said to Joseph, “See, I have set you over all the land of Egypt.” Then Pharaoh took his signet ring from his hand and put it on Joseph’s hand, and clothed him in garments of fine linen and put a gold chain around his neck. And he made him ride in his second chariot. And they called out before him, “Bow the knee!” Thus he set him over all the land of Egypt.

Some scholars argue that Joseph could not have ruled over “all of Egypt” if he served under a Hyksos king, given that the Hyksos primarily controlled Lower Egypt while Upper Egypt remained under native Egyptian rule. However, the phrase “all the land of Egypt” in the biblical text must be understood within its historical context. Even though the Hyksos did not control Upper Egypt, they exercised suzerainty over the land, collecting tribute from Thebes and exerting influence beyond their direct rule, as evidenced by Kamose’s stela, documenting Thebes’ status as a vassal state paying taxes to the Hyksos. In these inscriptions, Kamose expresses his determination to liberate Egypt from foreign rule, highlighting the oppressive taxation imposed by the Hyksos on the Egyptian populace.[32]

Thus, when Genesis states that Joseph ruled over “all of Egypt,” it is fully consistent with the historical reality of the Hyksos period. His elevation to a high administrative role, likely equivalent to the Egyptian vizier, further aligns with the Hyksos period. The economic transactions orchestrated by Joseph, in which he accepted payments, including land, in exchange for grain, bear striking parallels to how the Hyksos may have solidified their control over Egypt (Genesis 47:13-26). His administrative power extended over the most fertile and economically vital regions of Egypt and, by extension, any territories under their dominion.

Joseph’s Marriage to Asenath: Evidence of Native or Hyksos Ruler?

Another argument often used to place Joseph in the Middle Kingdom rather than the Second Intermediate Period is his marriage to Asenath, the daughter of Potiphera, priest of On (Genesis 41:45). Some suggest that such a union implies Joseph served under a native Egyptian ruler rather than a Hyksos king. However, this argument overlooks the political nature of ancient marriages and the hybrid administrative structure of the Hyksos period, which blended Egyptian and Semitic governance.

Joseph’s marriage to Asenath was arranged by Pharaoh himself (Genesis 41:45), indicating that it was likely a political decision rather than a personal choice. Egyptian priests held immense power and influence in Egyptian society. Although it was common for high officials to marry into local aristocracies to consolidate power and unify diverse populations in the ancient Near East, it was extremely rare for a Pharaoh to arrange a marriage between an Egyptian priest’s daughter and a foreigner. If a native Egyptian Pharaoh had promoted Joseph, such a marriage would have been highly controversial. However, if Joseph served under a Hyksos king, then his marriage to the daughter of a prominent Egyptian priest may have been designed to bridge the cultural dividebetween the foreign Semitic rulers and the native Egyptian elite.

This scenario aligns with the broader political landscape of the Hyksos period, during which Semitic rulers sought alliances with native Egyptian institutions to solidify their control over Egypt. By marrying into the priestly family of On, Joseph’s position as Pharaoh’s second-in-commandwould have been more acceptable to the Egyptian populace, as it linked him to an established religious power structure.

However, despite this marital alliance, thebiblical text provides no indication that Joseph adopted Egyptian religious practices. On the contrary, his faith in Yahweh remained steadfast, as evidenced in the naming of his sons and his final request to be buried in the Promised Land (Genesis 50:25).

Despite being non-natives, the Hyksos did not impose an entirely separate religious system but, instead, engaged in a syncretic blending of Semitic and Egyptian religious traditions. While the Hyksos are often associated with the worship of Seth—whom they may have identified with the Canaanite storm god Ba’al—their religious practice was far more inclusive. Scarabs from the Hyksos period display representations of various deities exhibiting both Egyptian and Asiatic characteristics, indicating that the Hyksos did not restrict themselves to the worship of a single god.[33] Instead, they incorporated Egyptian deities into their religious framework, merging them with their own traditions in a way that was both practical and politically advantageous.

This syncretic approach suggests that the Hyksos rulers sought to placate and integrate Egypt’s existing religious institutions rather than alienate them. The powerful priesthood of Ra, centered at Heliopolis (On), was a dominant force in Egyptian religious and political life, and the Hyksos would have needed their support—or at the very least, their neutrality—to maintain stability. The priesthood of Ra was not sidelined or rendered irrelevant during Hyksos rule; rather, their continued presence and influence are evident in the marriage alliance between Joseph and Asenath.

By arranging this marriage, the Hyksos ruler demonstrated a deliberate effort to establish lasting peace between his administration and the powerful Egyptian religious elite. If the priesthood of Ra had been entirely opposed to Hyksos rule, such an alliance would have been unthinkable. Instead, this union suggests a level of cooperation and mutual accommodation. The willingness of the On priesthood to enter into such a political and familial agreement indicates that they were not powerless under the Hyksos but retained significant religious and political influence.

This approach aligns with broader Egyptian religious traditions, in which foreign gods were often absorbed rather than rejected outright. The Hyksos’ adoption of Egyptian customs, including religious syncretism, was a strategic move to legitimize their rule and ensure stability. Rather than being iconoclastic conquerors, they appear to have understood the necessity of integrating into the Egyptian world they governed.

Joseph’s marriage into the priestly elite of On, therefore, is not an argument against his presence in the Hyksos period, but further confirmation of the Hyksos’ pragmatic approach to governance, in which Egyptian institutions were maintained and even strengthened through diplomatic and religious integration. Aligning Joseph, a fellow Semite, with an Egyptian priestly family would have been a calculated move by the Hyksos Pharaoh to strengthen ties with the native Egyptian elite. Such a marriage would have helped legitimize Hyksos rule, ensuring the support of the powerful religious establishment while also integrating Joseph more fully into the administration.

Cultural and Dining Separations Between Egyptians and Asiatic Peoples

Another crucial textual clue supporting Joseph’s Hyksos context is the account of the meal he shared with his brothers and the Egyptians: “They served [Joseph] by himself, the brothers by themselves, and the Egyptians who ate with him by themselves, because Egyptians could not eat with Hebrews, for that is detestable to Egyptians” (Genesis 43:32). The dining scene involving Joseph, his brothers, and the Egyptians (Genesis 43:31-34) took place in Joseph’s own residence, not in the royal palace. Joseph, being second-in-command to Pharaoh, would have possessed a grand private dwelling staffed by Egyptian servants under his authority (Genesis 43:16-17). It is also important to note that, in this context, Joseph had not yet revealed who he was and so this dinner was not only staged as such, but it also highlights several key cultural and social dynamics at play in this event.

This verse highlights a cultural and ethnic separation that was strictly maintained within Egypt. Why would the Egyptians refuse to eat with Joseph’s brothers? The likely explanation is that Egyptians considered dining with foreigners, especially shepherds from Canaan, as ritually impure or detestable (Genesis 43:32). While Joseph had fully integrated into Hyksos rule, the native Egyptian elite still looked down upon Semitic peoples—a sentiment later reinforced by Manetho’s anti-Hyksos rhetoric, in which he describes them as a “diseased” people unfit to rule.[34] High-ranking individuals, like Joseph in the biblical narrative, also dined separately, underscoring their elevated status. These practices highlight the Egyptians’ commitment to preserving social distinctions and religious purity, leading them to avoid communal dining with foreigners.[35]

Thus, Joseph’s household set three separate tables: one for Joseph, one for his brothers, and another for the Egyptian attendants. Moreover, Joseph’s deliberate seating arrangement of his brothers by age astonished them (Genesis 43:33), serving as subtle proof of his unique insight into their identities. This carefully staged meal also prepared the way for Joseph’s subsequent revelation of his true identity (Genesis 45).

This ethnic and dietary separation suggests that:

- Joseph’s Hyksos overlords had adopted Egyptian administrative structures but still recognized ethnic distinctions. Native Egyptian elites remained culturally separate from the ruling Semites.

- The Hyksos had to placate native Egyptians who resented being ruled by foreigners. Maintaining strict ethnic boundaries at formal events helped avoid tensions.

If Joseph had been serving a native Egyptian king, we would not expect this clear ethnic distinction between Hebrews and Egyptians at the dining table because a native Pharaoh would never have even eaten with an Asiatic person. However, in the Hyksos period, such distinctions would have been actively enforced to maintain political stability.

Scholars point out that this detailed description aligns well with Egyptian cultural practices of the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1549 B.C.) during Hyksos rule, reinforcing arguments that Joseph’s narrative fits best within this historical context. The scene underlines Joseph’s dual identity—deeply Egyptianized yet ultimately Hebrew—highlighting his delicate position bridging two distinct cultural worlds.

The Broader Cultural and Political Implications

The cultural divisions in Genesis 43:32 and Genesis 46:34 provide significant historical and archaeological support for the short sojourn model, placing Joseph’s rise within the Hyksos period rather than the 12th Dynasty.

- Egyptian Ritual Purity and Food Taboos

- Egyptians had strict purity laws, and dining customs were tied to ethnic and religious identity. Foreigners, especially Semites, were often considered impure.[36]

- Political Balancing Act: Hyksos Tolerance for Egyptian Customs

- The Hyksos would not have shared the native Egyptian disdain for shepherds or Semitic customs, but they needed to balance their own ethnic heritage with their rule in Egypt to navigate the delicate cultural divide.

- Joseph, as a Hebrew, could thrive under a Hyksos administration, but this does not mean all Egyptians would have accepted his family as equals. Joseph had resided in Egypt long enough to assimilate into its culture, adopting Egyptian customs, language, and even taking an Egyptian name and wife. In contrast, his brothers remained outsiders, unfamiliar with Egyptian practices and societal norms.

- Maintaining strict ethnic separations at meals (Genesis 43:32) and reinforcing Egyptian distaste for shepherds (Genesis 46:34) would have helped them keep peace with the Egyptian elite.

Joseph’s Instructions to His Brothers: Egyptian Contempt for Shepherds

When Joseph prepared his brothers for their audience with Pharaoh, he gave them unusual instructions: “You should say, ‘Your servants have tended livestock from our boyhood on, just as our fathers did.’ Then you will be allowed to settle in the land of Goshen, for all shepherds are detestable to the Egyptians” (Genesis 46:34). The ancient Egyptians were primarily an agrarian society, placing high value on farming and land cultivation. Shepherds, often associated with nomadic lifestyles, were viewed with suspicion. This cultural bias likely stemmed from the Egyptians’ preference for settled agricultural life over the perceived unpredictability of nomadic shepherding.

However, on the surface, this passage raises an immediate question: If shepherds were so detestable to the Egyptians, why would Joseph deliberately tell his brothers to emphasize their identity as shepherds? If Joseph were speaking to a native Egyptian pharaoh, this strategy would make no sense—it would risk rejection rather than favor. The most logical explanation is that Joseph was addressing a Hyksos ruler who, unlike native Egyptians, was likely involved in pastoral activities himself and would not share the same cultural disdain for shepherding. Such information would help the pharaoh select an appropriate location for Joseph’s family that was well suited for shepherding and unlikely to cause friction with the native Egyptians.

This distinction between Hyksos and native Egyptians aligns with what we know from both archaeological evidence and Egyptian propaganda against the Hyksos. Ancient Egyptian sources—including Manetho’s account—describe the Hyksos as “Asiatics” who ruled as shepherd-kings, bringing with them foreign customs and practices.[37] Ian Shaw further confirms that Hyksos rulers were deeply involved in animal husbandry, a key economic activity of the Levantine Semitic peoples who migrated into Egypt during the Middle Bronze Age.[38] Thus, Joseph’s advice to his brothers makes the most sense if Pharaoh was a Hyksos king who would sympathize with their pastoral background rather than a native Egyptian ruler who would have viewed them with disdain.

Pharaoh Entrusting His Own Flocks to Joseph’s Family

Further reinforcing the Hyksos context is the extraordinary generosity of Pharaoh toward Joseph’s family, specifically, his request that Joseph’s brothers tend the royal livestock: “The land of Egypt is before you; settle your father and your brothers in the best part of the land. Let them live in Goshen. And if you know of any among them with special ability, put them in charge of my own livestock” (Genesis 47:6). This passage reveals several key points:

- He offers the Hebrews the most fertile land. This suggests a ruler with an interest in promoting shepherding, which fits Hyksos priorities, as they were a Semitic ruling class with strong pastoral traditions.

- The directive for Joseph’s family to oversee Pharaoh’s livestock, despite Joseph’s high rank as Pharaoh’s second-in-command and the traditional Egyptian aversion to shepherds, suggests a departure from native Egyptian customs. Joseph’s rise to prominence in Egypt is well-documented in the biblical account and given this esteemed position, it would be culturally incongruous for a native Egyptian Pharaoh to assign Joseph’s family—a family associated with a profession deemed detestable—the responsibility of managing royal livestock. Such an act could be perceived as a diminution of Joseph’s status and an affront to Egyptian societal norms.

- He entrusts Semites with royal livestock. This action strongly contradicts the known Egyptian attitude toward Asiatic peoples during periods of native rule, as Semitic peoples were often viewed as outsiders or even enemies in later Egyptian texts.[39]

Thus, the Joseph narrative aligns perfectly with the known historical and political realities of the Hyksos period:

- It is unlikely that a native pharaoh would have been as enthusiastic about shepherding or would have immediately entrusted the royal herds to Semitic foreigners.

- The Hyksos’ Semitic background and potential association with shepherding could explain a more favorable disposition toward Joseph’s family and their occupation that may have made this pharaoh more likely to trust them so quickly with his own flocks. Under Hyksos rule, assigning the management of royal flocks to experienced shepherds like Joseph’s brothers would be pragmatic and culturally acceptable.

The Chariot and the Short Sojourn: Aligning Joseph’s Narrative with the Hyksos Period

One of the most compelling arguments for placing Joseph within the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1549 B.C.) under Hyksos rule rather than the Middle Kingdom (ca. 1878-1843 B.C.) is the biblical mention of chariots in his story. Genesis 41:43 describes Joseph riding in Pharaoh’s chariot, a term that appears again in Genesis 46:29, where Joseph harnesses his chariot to meet his father in Goshen. The term is used again in Exodus 15:4 to describe Pharaoh’s chariot-riding army.

- Genesis 41:43 states that Joseph rode in Pharaoh’s chariot. The Hebrew word merkabah (מֶרְכָּבָה) appears here for the first time in the biblical text. While the term can broadly refer to a vehicle, the context suggests a prestigious, high-status mode of transport, more akin to a war chariot than a simple cart.

- Genesis 46:29 describes Joseph harnessing his chariot (אָסַר, asar) to go meet his father, which explicitly implies the presence of a horse-drawn vehicle, rather than a hand-pulled wagon.

- Exodus 15:4 confirms that Pharaoh’s army later perished in the Red Sea while riding in chariots(merkabah), indicating that by this time, war chariots were well established in Egypt.

Could Chariots Have Been Used in the 12th Dynasty?

Some scholars argue that primitive wheeled vehicles may have existed in the 12th Dynasty, over 100 years before the Hyksos. However, these were likely ox-drawn sledges or wooden wagons, not the light, horse-drawn chariots that later revolutionized Egyptian warfare. Donald B. Redford, Manfred Bietak, and Ian Shawnote that prior to the Second Intermediate Period, the Egyptians primarily relied on foot soldiers and archers, with no evidence of chariotry in military or ceremonial contexts.[40] Ian Shaw and Alan R. Schulman confirm that chariots became a widespread military and ceremonial vehicle only after the Hyksos introduced them. By the later 18th Dynasty (ca. 1549-1298 B.C.), chariots were used extensively in royal processions and hunting expeditions.[41] The argument for a 12th Dynasty chariot relies on speculation, as no archaeological remains of horse-drawn vehicles from this period have been found.

A Chariot in the Context of the Hyksos Period

While the invention of the light, two-wheeled war chariot is generally credited to Indo-Iranian cultures around 2000 B.C., its introduction into Egypt is most often linked to the arrival and dominance of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1550 B.C.).[42] Leonard Cottrell similarly observes that the chariot design associated with the Hyksos—light, two-wheeled, and spoked—first appeared in the Near East and spread westward through trade, migration, and conquest, culminating in its adoption by the Hyksos in Egypt.[43] Kenneth Kitchen and Ian Shaw confirm that the Hyksos brought technological innovations, including advanced composite bows, bronze weapons, and the chariot, which they used effectively to dominate northern Egypt.[44] The prevailing scholarly consensus holds that horse-drawn war chariots were introduced to Egypt by the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period and were unknown in Egypt before their arrival.

Archaeological discoveries at Tell el-Dab’a (ancient Avaris), the Hyksos capital, provide substantial evidence supporting this historical trajectory. Excavations at the site have revealed horse burials and associated material remains from the Hyksos period, strongly suggesting that it was this Asiatic population that introduced horses and chariot technology to Egypt.[45] While the organic materials of chariot construction rarely survive archaeologically, the finds at Avaris—together with later Egyptian textual references—support the argument that the war chariot appeared in Egypt during the Hyksos era.

Egypt, by contrast, appears to have been relatively isolated from this technological development during the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom.[46] Despite sustained diplomatic and trade contacts with the Levant, there is no textual or material evidence that native Egyptians adopted the war chariot during this time. Though it is plausible that Egyptians were aware of such technology, whether due to military conservatism or lack of access to horses, they did not incorporate chariot warfare until the end of the Second Intermediate Period.[47] Bietak notes the following:

The light horse-drawn chariot is an Asiatic invention and was also, as it seems, introduced during Hyksos rule in Egypt…The Egyptians adopted the use of the chariot from the Hyksos and seem to have already been using it in the final battle against Avaris, as shown by representations from the temple of Ahmose in Abydos.[48]

The Egyptians of the 18th Dynasty (New Kingdom) later depicted the Hyksos as barbaric invaders, emphasizing their foreign customs—such as the use of chariots—as a stark contrast to native Egyptian tradition.[49] Notably, the biblical “Pharaoh who did not know Joseph” (Exodus 1:8) likely refers to an Egyptianruler of the 18th Dynasty who had overthrown the Hyksos, explaining the sudden shift in policy toward the Israelites.

Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that this argument is, in part, built on the absence of earlier evidence. The lack of material proof of chariotry prior to the Hyksos does not definitively preclude the possibility that future discoveries could reveal earlier Egyptian exposure to the chariot. Should clear evidence of chariot use in Egypt predating the Hyksos period emerge, it would require a reconsideration of the current historical reconstruction.

However, as the evidence presently stands, the convergence of archaeological, cultural, and biblical data aligns precisely with the biblical timeframe in which Joseph and his family arrived. The mention of chariots in Joseph’s story supports the short sojourn model and aligns with his rise under Hyksos rule, rather than in the Middle Kingdom. Long sojourn proponents’ claims that chariots existed in the 12th Dynasty rest on hypothetical reconstructions of primitive wooden carts, not the horse-drawn vehicles described in Genesis. The strongest historical and archaeological evidence points to the introduction of true chariots by the Hyksos, making Joseph’s high-status use of one entirely consistent with a Second Intermediate Period timeframe.

THE RAPID POPULATION GROWTH OF THE ISRAELITES IN EGYPT

The question of how the Israelite population grew so rapidly during their time in Egypt has been a central objection to the short sojourn model. Critics argue that 215 years is insufficient for Jacob’s family—recorded as 70 individuals in Genesis 46:27—to expand into the two to three million estimated at the time of the Exodus. However, a careful examination of biblical evidence, demographic modeling, and historical context demonstrates that such rapid growth is not only feasible but entirely consistent with the biblical record.

Biblical Testimony of Israel’s Growth

The Bible explicitly describes an extraordinary period of population increase among the Israelites:

- Exodus 1:7—“But the children of Israel were fruitful, and increased abundantly, and multiplied, and waxed exceedingly mighty; and the land was filled with them.”

- Exodus 1:12—“But the more they afflicted them, the more they multiplied and grew. And they were grieved because of the children of Israel.”

- Exodus 1:20—“Therefore God dealt well with the midwives: and the people multiplied, and waxed very mighty.”

The wording in these passages underscores an unusually high growth rate, implying that divine providence played a role in ensuring the multiplication of the Israelites. Furthermore, the conditions under which they lived—favorably in Goshen before their oppression—would have supported significant demographic expansion.

Was 70 the True Starting Number?

A common misinterpretation of the biblical text assumes that the 70 individuals recorded in Genesis 46:27 represented the entire Israelite population at the time of entry into Egypt. However, at least two factors suggest the actual number was higher:

- Wives and Uncounted Family Members—Genesis 46:26 clarifies that the 70 excluded the wives of Jacob’s sons. Additionally, while Jacob’s granddaughters are referenced in plural form, only one (Serah, daughter of Asher) is named, suggesting more unnamed female descendants.

- The Septuagint and New Testament Evidence—The Greek Septuagint translation states that 75 people entered Egypt, a number referenced by Stephen in Acts 7:14, where he states, “Joseph sent and called his father Jacob and all his relatives to him, seventy-five people.” This total likely includes the wives of Jacob’s sons.

Demographic Feasibility: Could the Israelite Population Grow This Fast?

Even with a modest starting population, favorable conditions could have enabled rapid growth. Key factors include:

- High Fertility Rates—In the ancient Near East, large families were common, with many women bearing six to ten children. This aligns with God’s promise of fruitfulness to Abraham’s descendants (Genesis 17:6).

- Short Generational Intervals—If each generation began having children around 20-25 years of age, the population could double approximately every 16 to 20 years. Over 215 years, this would allow for seven to ten generations, producing exponential growth.

- Low Mortality and Favorable Living Conditions—The Israelites initially thrived in Goshen, a fertile and agriculturally rich region, meaning they had adequate food and resources to sustain high population growth. The absence of war and urban disease also contributed to survivability.

Would 430 Years Be a Better Fit?

Critics who advocate for a 430-year sojourn in Egypt argue that it allows for more gradual population growth. However, this view faces significant textual, genealogical, and historical problems:

- Genealogical Constraints—The genealogies in Exodus and Numbers do not support 430 years. For example, Moses is only four generations removed from Levi (Levi → Kohath → Amram → Moses, Exodus 6:16-20). A 430-year sojourn would require extremely long lifespans or skipped generations.

- Exponential Growth vs. Slow Growth—Exodus emphasizes that the Israelites multiplied “exceedingly,” suggesting rapid growth, not a slow increase over four centuries.

- Alignment with Egyptian History—The short sojourn aligns better with Egyptian history. A 215-year stay places the oppression under the 18th Dynasty, whereas a 430-year sojourn forces Joseph’s rise to power into the 12th Dynasty (ca. 1900-1800 B.C.), a period that lacks supporting archaeological and historical evidence.

The Short Sojourn and Population Growth Are Historically Plausible

The argument that 215 years is too short for the Israelites to grow into a nation of millions is not supported by demographic models, biblical genealogies, or historical evidence. The Israelite population was likely much larger than 70 upon entering Egypt, and given high fertility rates, large families, and short generational intervals, a natural expansion into the millions is probable. Rather than being an argument against the short sojourn model, the population growth of Israel strongly supports it.

CONCLUSION

Thus, the short sojourn model, which places Joseph’s rise to power in the Hyksos period, remains the most historically, textually, and archaeologically defensible interpretation. The alternative 12th Dynasty placement (ca. 1878-1843 B.C.) under a native Egyptian ruler contradicts the biblical text and Egyptian historical realities. This study has sought to prioritize the biblical text above archaeological and historical data while demonstrating how these external sources help clarify and reinforce key details. The narrative elements within Genesis and Exodus—such as Joseph’s shaving before appearing before Pharaoh, the command for his brothers to emphasize their shepherding profession, his marriage to an Egyptian priest’s daughter, and his use of a chariot—align far more naturally with a Hyksos-era setting than with the Middle Kingdom.

The political and social environment of pre-Hyksos Egypt does not support the idea of a foreigner like Joseph rising to prominence. The native Egyptian dynasties maintained a strict cultural and ethnic identity, making it highly unlikely that a Semitic foreigner would be elevated to a position of such immense authority. By contrast, the Hyksos, themselves of Semitic origin, would have been far more inclined to promote a fellow Semite to a position of power, particularly one who demonstrated extraordinary administrative abilities. While some scholars insist on a Middle Kingdom setting, this argument is primarily driven by chronological constraints, not by historical or biblical consistency.

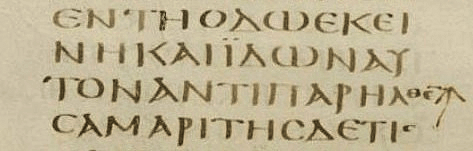

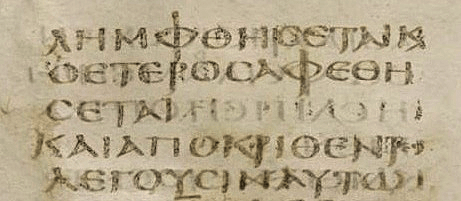

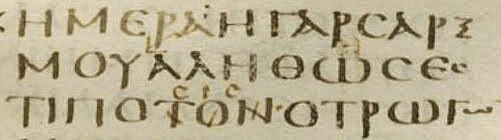

The evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that Joseph rose to power during the Hyksos period, making the biblical account fully coherent with both archaeological and historical data. The short sojourn model allows for a clearer understanding of when Abraham traveled to Egypt, when Joseph and Jacob arrived, and how these events led to the defining moment of Israel’s history—the Exodus. Paul’s statement in Galatians 3:17 affirms that the 430-year period began with Abraham’s time in Canaan, not solely with Israel’s stay in Egypt. This interpretation, supported by the Septuagint and Samaritan Pentateuch, confirms that Israel’s actual residence in Egypt lasted 215 years. While no single piece of evidence offers absolute confirmation, the combined biblical, historical, and archaeological data present a strong and well-reasoned case.

Joseph’s story reflects a broader narrative of divine providence, as God used even his imprisonment to place him in Pharaoh’s service (Genesis 41:14-41). The racial and political dynamics of his time add depth to his journey from slave to overseer to prisoner to ruler, demonstrating how God’s plan unfolds even in the midst of human conflict and societal divisions (Genesis 50:20). From this perspective, the alignment of the Hyksos reign and the account of Joseph’s rise to power could be seen as more than coincidental—it is the providence and power of God.

ENDNOTES

1 “Semitic” refers to ancient peoples originating from the Near East who spoke related languages such as Hebrew, Aramaic, and Akkadian, and who historically migrated into regions like Egypt, influencing its cultural and social landscape.

2 D. Candelora (2017), “Defining the Hyksos: A Reevaluation of the Title hk3 h3swt and its Implications for Hyksos Identity,” Journal of the American Research Council in Egypt, 53:203-221.

3 John Van Seters (1966), The Hyksos, A New Investigation (New Haven, CT: Wipf and Stock).

4 Donald B. Redford (1993), Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University), p. 107.

5 Ibid., p.103.

6 J.M. Weinstein (1997), “Hyksos,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, ed. D.E. Meyers (Oxford: Oxford University), 3:133.

7 Alan H. Gardiner (April-July 1916), “The Defeat of the Hyksos by Kamose: The Carnarvon Tablet No. I,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 3[2/3]:95-110.

8 Redford (1993), p. 343.

9 Redford, Donald B. (1997), “Textual Sources for the Hyksos Period,” in The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer D. Oren (Philadelphia: The University Museum). For more on the papyrus, see Gay Robins and Charles Shute (1987), The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (London: British Museum).

10 Bietak, Manfred (1997), “The Center of Hyksos Rule: Avaris ‘Tel el-Dab’a,’” in The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer D. Oren (Philadelphia: University Museum), pp. 108-109; James Hoffmeier (1996), Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition (New York: Oxford), pp. 63-64.

11 The Levant is a region along the eastern Mediterranean coast, encompassing modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Cyprus, and northern Syrian areas.

12 Bietak, Manfred (1991), “Egypt and Canaan during the Middle Bronze Age,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 282:89; J.S. Holladay, Jr. (1997), “Tell el-Maskhuta,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, ed. D.E. Meyers (Oxford: Oxford University), 3:432-437. See also: J.S. Holladay, Jr. (1982), Cities of the Delta Part III: Tell el-Maskhuta: Preliminary Report on the Wadi Tumilat Project 1978-1979 (Malibu: Udena Publications), p. 63.

13 See Holladay (1997), “Tell el-Maskhuta;” John S. Holladay, Jr. (1997), “The Eastern Nile Delta During the Hyksos and Pre-Hyksos Periods: Toward a Systemic/Socioeconomic Understanding,” in The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer D. Oren (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum), pp. 183-252; Manfred Bietak (1987), “Canaanites in the Eastern Nile Delta,” in Egypt, Israel, Sinai: Archeological and Historical Relationships in the Biblical Period, ed. A.F. Rainey (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University), p. 43; Hoffmeier (1996), pp. 63-66; Kerry Muhlestein (2016), “The Exodus,” in A Bible Reader’s History of the Ancient World, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, Brigham Young University), pp. 119-132.

14 Manfred Bietak (2018), “The Many Ethnicities of Avaris: Evidence from the Northern Borderland of Egypt,” in From Microcosm to Macrocosm: Individual Households and Cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia, ed. Julia Budka and Johannes Auenmüller (Leiden: Sidestone), pp. 73-92; Chris Stantis, et al. (2020), “Who Were the Hyksos? Challenging Traditional Narratives Using Strontium Isotope (87Sr/86Sr) Analysis of Human Remains from Ancient Egypt,” PLoS ONE, p. 15.

15 Bietak notes that rapid expansion of “middle-hall” style houses and the rise in Semitic burial practices denote a significant shift in the population and cultural influence at the site. See Bietak (1997), “The Center of Hyksos Rule,” 97-99.

16 Manfred Bietak (2022), “Avaris/Tell el-Dab‘a,” in Encyclopedia of Ancient History, ed. Andrew Erskine, David B. Hollander, and Arietta Papaconstantinou (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.), p. 1-2; Bietak (1997), “The Center of the Hyksos Rule,” pp. 78-140.

17 J. Bourriau (2003), “The Second Intermediate Period (c.1650-1550 B.C.),” in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw (Oxford: Oxford University), pp. 172-206.

18 John Gee (2004), “Overlooked Evidence for Sesotris III’s Foreign Policy,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, pp. 23-31.

19 See Kenneth A. Kitchen (2003), On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans), p. 344.

20 See Daphna Ben-Tor, “The Sealings from the Administrative Unit at Tell Edfu: Chronological and Historical Implications,” in The Hyksos Ruler Khyan and the Early Second Intermediate Period in Egypt: Problems and Priorities of Current Research. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4-5, 2014, ed. Irene Forstner-Müller and Nadine Moeller (Vienna: Holzhausen, 2018).

21 Erik Hornung (1999), History of Ancient Egypt: An Introduction, trans. David Lorton (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University), p. 61; William C. Hayes (1955), A Papyrus of the Late Middle Kingdom in the Brooklyn Museum (New York: The Brooklyn Museum), p. 99.

22 Papyrus Brooklyn35.1446; Stephen Quirke (1990), “The Administration of Egypt in the Late Middle Kingdom: The Hieratic Documents” (New Malden, Surrey: SIA), pp. 127-154.

23 Joseph, in many ways, was just one among many enslaved Semites in Egypt (Genesis 37:36).

24 All emphasis of Scripture added by author.

25 Alexander Ilin-Tomich (2016), “Second Intermediate Period,” in UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, ed. Willeke Wendrich, Jacco Dieleman, and Elizabeth Frood (Los Angeles: University of California); Lutz Popko (2016), “Late Second Intermediate Period to Early New Kingdom,” in UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, ed. Willeke Wendrich, Jacco Dieleman, and Elizabeth Frood (Los Angeles: University of California).

26 Stephen Quirke (2004), “Identifying the Officials of the Fifteenth Dynasty,” in Scarabs of the Second Millennium BC from Egypt, Nubia, Crete and the Levant: Chronological and Historical Implications, Papers of a Symposium, Vienna, 10–13 January 2002, ed. Manfred Bietak and Ernst Czerny (Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften), pp. 171-193.

27 William Kelly Simpson (2003), “The Kamose Texts,” in The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry, ed. William Kelly Simpson (New Haven and London: Yale University), third edition, p. 348; Roxana Flammini (2015), “Building the Hyksos’ Vassals: Some Thoughts on the Definition of the Hyksos Subordination Practices,” Ägypten und Levante XXV, p. 240.

28 Manuscript B, 222-223; R. Koch (1990), “Die Erzählung des Sinuhe,” Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca, (Bruxelles: Édition de la Fondation Reine Élisabeth), 17:66-67.

29 Papyrus Hermitage 1116B, ll, 18-19.

30 Wolfgang Helck (1992), Die Prophezeiung des Nfr.tj, 2nd ed. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz), p. 18; Wolfgang Helck (1971), Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3, und 2, Jahrtausend v. Chr., 2nd ed. (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz), pp. 39d-40.

31 Charles F. Aling (Fall 2002), “Joseph in Egypt,” Bible and Spade (Second Run), 15[4].

32 Gardiner (1916), “The Defeat of the Hyksos by Kamose,”95-110.

33 Van Seters (1966), The Hyksos: A New Investigation, p. 177.

34 Josephus, Against Apion 1.14.

35 James M. Freeman (1972), Manners and Customs of the Bible (New Kensington, PA: Whitaker House).

36 D. B. Redford (1993), Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University).

37 Josephus, Against Apion 1.14.

38 Ian Shaw (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University).

39 Redford (1993), Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times.

40 Redford (1993), Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times; Manfred Bietak (2014), “The Middle Bronze Age of the Levant: A Changing Picture,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000-332 BCE, ed. Margreet L. Steiner and Ann E. Killebrew (Oxford); and Shaw (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt.

41 Ian Shaw (2001), “Egyptians, Hyksos and Military Technology: Causes, Effects or Catalysts?” in The Social Context of Technological Change: Egypt and the Near East, 1650-1550 BC, ed. Andrew Shortland (Oxford: Oxbow Books), pp. 59-72; Alan R. Schulman (1980), “Chariots, Chariotry and the Hyksos,” Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities, 10:105-154.

42 Alfred S. Bradford (2001), With Arrow, Sword and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World (Westport, CT: Praeger), p. 13; Roberto A. Díaz Hernández (2015), “The Role of the War Chariot in the Formation of the Egyptian Empire in the Early 18th Dynasty,” Studien zur Ägyptischen Kultur, 43:109-122.

43 Leonard Cottrell (1969), The Warrior Pharaohs (New York: GP Putnams Sons), p. 57.

44 Kenneth A. Kitchen (2003), On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 349-350,358-360; and Ian Shaw (2012), Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation: Transformations in Pharaonic Material Culture (London: Bloomsbury).

45 Manfred Bietak (2011), “The Aftermath of the Hyksos in Avaris,” in Culture Contacts and the Making of Cultures: Papers in Homage to Itamar Even-Zohar, ed. Rakefet Sela-Sheffy and Gideon Toury (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University), p. 33. See also: Boessneck, J. (1976), “Tell el-Dabʻa III: Die Tierknochenfunde 1966-1969,” Untersuchungen der Zweigstelle Kairo des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes 3, DÖAW 5 (Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften); Boessneck, J. and A. von den Driesch (1992), “Tell el-Dabʻa VII: Tiere und historische Umwelt im Nordost-Delta im 2,” Jahrtausend v. Chr. anhand der Knochenfunde der Ausgrabungen 1975–1986. Untersuchungen der Zweigstelle Kairo des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes 10, DÖAW 11 (Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften).

46 A.J. Veldmeijer & S. Ikram (2013), Chasing Chariots. Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference, Cairo 2012 (Leiden: Sidestone), p. 101.

47 M.A. Littauer and J.H. Crouwel (1979), Wheeled Vehicles and Ridden Animals in the Ancient Near East (Leiden: Brill).

48 Bietak (2011), “The Aftermath of the Hyksos in Avaris,” p. 33.

49 Shaw (2012).

REPRODUCTION & DISCLAIMERS: We are happy to grant permission for this article to be reproduced in part or in its entirety, as long as our stipulations are observed.