New Research: Humans and Chimps Do Not Share 98% of Their Genomes

New Research: Humans and Chimps Do Not Share 98% of Their Genomes

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The following article was written by A.P. auxiliary staff scientist Dr. Joe Deweese who holds a Ph.D. in Biochemistry from Vanderbilt University and serves as Professor of Biochemistry and Director of Undergraduate Research at Freed-Hardeman University.]

Introduction

With the sequencing of the human genome in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we crossed a new threshold in our understanding of the information contained within our cells.1 But what does that even mean? And why does it matter if we have the genome sequences anyway? Let us review what DNA is and how sequencing works before we explore some recent findings that impact our understanding of human and chimp DNA differences.

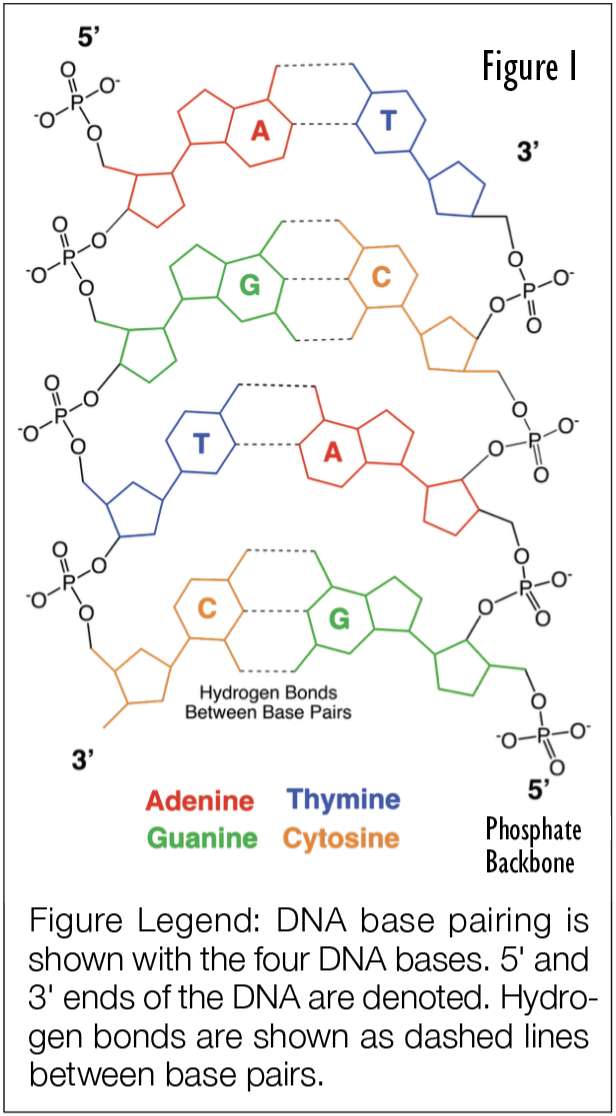

The major information storage molecule in our cells is DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid. It should be noted that information appears also to be stored in other ways than the DNA sequence alone (e.g., epigenetics, spatial information, and other forms). DNA is a double-stranded polymer of nucleotide bases—we call them A, T, C, and G for short (see Figure 1). These bases are arranged in sequences (e.g., like letters combining to form words and sentences) that encode information about building proteins and for controlling how and when portions of the DNA are used. Interestingly, only about 2% of the human genome encodes proteins. Yet, the ENCODE project demonstrated in 2012 that 80%+ of the human genome has biochemical function, which implies that there are many other functions for DNA other than encoding proteins.2

The entire collection of DNA in an organism is called its genome. In eukaryotic organisms, like humans, animals, and plants, the DNA is arranged into a series of molecules we call chromosomes. Humans have 46 chromosomes in our body cells—23 inherited from our father and 23 from our mother (see Figure 2). We further break these chromosomes down to autosomes (chromosomes 1-22) and sex chromosomes (X and Y). Interestingly, we have sequenced enough human genomes that we can conclude that any two humans differ by less than 1%!

DNA sequencing involves extracting DNA from the cells of an organism and using various approaches to determine what are the exact sequences of DNA bases (i.e., the letters of the DNA language). In the case of genome sequencing, this involves the goal of gathering every DNA letter representing the entire genome of the organism. While the initial sequencing of the human genome took several years, millions of dollars, and an untold number of hours of research, modern sequencing has rapidly decreased the cost and increased the speed of the process. Modern sequencing methods can gather the equivalent of the entire human genome in a matter of hours on a single device! The cost has also decreased to the point that an entire human genome can be sequenced for a few hundred dollars.

Of course, our sequencing efforts did not stop with humans. At this point, the genomes of thousands of plants and animals have been sequenced, not to mention many thousands of bacterial and viral genomes. Huge online databases now provide researchers access to seemingly countless sequences.

Soon after the conclusion of the human genome project in 2004, the initial chimp genome sequencing was completed and published in 2005.3 With that, researchers began comparing DNA sequences between humans and chimps. Within the Darwinian paradigm, humans are the descendants of ape-like ancestors, which makes chimpanzees our distant cousins. This ancestry creates a prediction: if humans and chimps are related, we should share a large amount of genetic information. To state that another way: the closer our DNA sequences, the more genetically related we are. In an evolutionary view, this is used to estimate how long ago the human and chimp branches diverged from each other.

This prediction about similarity appeared to be confirmed in 2005 with the publication of the chimp genome. The estimates were that humans and chimps shared 98.8% of their genomes.4 This number has been touted by evolutionists and Darwin defenders for 20 years in support of the idea that humans and chimps are genetically related through common descent. It’s been on magazine covers and in news articles…case closed, right? Or is there more to the story?

There are separate questions that come to mind here: if we share that much of our DNA, does that prove anything about ancestry? No, not necessarily. This similarity could still result from the work of a Designer. After all, Scripture says nothing about the genetic similarity between humans and any other creature.5 So, what does that mean about genetic information? Well, if we are 98.8% similar, that 1.2% apparently makes a huge difference! After all, chimps live in the wild or in zoos, while humans get up each day and design computers and rockets and symphonies. But there is more to the story. To understand the difference, we need to dig a bit deeper into how sequencing is accomplished.

Borrowing the Framework

There are reasons to question the 98.8% similarity figure. One reason has to do with how the original chimp genome was constructed. When a genome is sequenced, the sequence information must be carefully assembled. The human genome sequencing was a massive task—both due to the sequencing technology but also due to the huge amount of DNA in the genome (humans have 3.2 billion DNA letters in one copy of our genetic code!). Chimps and other apes have genomes in the same size range as humans. DNA sequencing involves gathering fragments—kind of like paragraphs and chapters of a book. These fragments may start in the middle of a “paragraph” or “chapter” and end elsewhere. To assemble these into the “book,” researchers need to have many copies of each region to ensure they know where “paragraphs” and “chapters” start and end. As you can imagine, if you have enough pieces that overlap at different points, you can get the whole “book” compiled. Oftentimes, this requires each letter of the genome to be sequenced 60, 90, or even 100 times or more! They take all these fragments of DNA sequences and use powerful computers to reassemble them into a continuous sequence using portions that overlap between reads (see Figure 3). Of course, there is a lot more to the process of genome assembly, but this basic picture is enough to understand some of the technical challenges.

To simplify things in producing the chimp genome, researchers utilized portions of the human genome to build a scaffold or framework upon which they could build the chimp genome.6 For instance, having knowledge of key regions of each chromosome can help place certain sequences in order, and knowing which sequences are associated with which chromosomes can aid in proper placement. This is kind of like having a map showing major section and chapter breaks in a book. Such a map would certainly speed up the process of genome “assembly.” As you might imagine, however, this process could bias the results and make the genomes look more alike than they actually are.7 But how could we prove that? It would take a resequencing and assembly of the entire chimp genome without using a human genome framework.

Another reason to question the percent similarity is that such a direct correlation between two genomes is very hard to do. Consider this simplified analogy. If you own a car, there is likely an owner’s manual in the glove compartment. This manual probably has various versions depending on the model and trim level of the car from the same manufacturer. What if we took an owner’s manual from two similar cars and compared them? There would likely be some sections that are identical. There are likely other sections that are different based upon different features. There may also be sections that are found in one but not the other manual. How would you compare these two books? Sections that are shared between them would be easy to compare. But how do you quantify differences where something is missing in one manual but found in the other? Or, what if things are in a different order? Does that count as a difference? This leads to the need for more complex questions and details to quantify the differences. Arriving at a single number is no small task given these complexities, and it requires making somewhat arbitrary decisions about how to calculate a final value.

Resequencing and Reassembly of the Genome

While the 98.8% number has been used and quoted for two decades now, new research has been published that upends that claim. A large collaboration of researchers took on the task of completely resequencing and reassembling the entire chimp genome from telomere to telomere (i.e., end to end) for each chromosome, and they published their work in the prestigious journal Nature in April 2025.8 This impressive work is no small feat even with advanced next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques and more powerful computational tools for dealing with genetic information. Note that not only did they sequence chimpanzees, they sequenced a total of six ape genomes, including bonobo, gorilla, and orangutan.

The authors acknowledge that previous ape genomes have relied on the human genome structure as a scaffold on which to build the ape genomes, and part of their goal was to remove this sort of bias in constructing the genome.9 It is worth pointing out that the human genome has been refined several times in the last two decades and the final portions that were difficult to sequence have largely been resolved.10 Further, the authors of this latest study note that these latest versions of ape genomes still need additional work in some of the more difficult-to-sequence areas.

While the focus of the new paper is to report on these genomes and what can be learned from these new assemblies, the authors include supplemental information files that share additional data and comparisons. Buried within this information are comparisons between ape and human genomes. These comparisons give us some idea of how similar the genomes are. What did they find?

When human and chimp genomes are compared, there is a 1.6% single nucleotide divergence.11 In a sense, this means that for the sequences that are found in both human and chimp genomes, 98.4% of the nucleotides line up. But that doesn’t sound so different from 98.8%. So, perhaps the number has been correct?

There is more to account for in this calculation. Just as with our owner’s manual illustration, the human and chimp genomes do not share all the same sequences and regions. To quantify these regions, the authors also report what is called “gap divergence.” Gap divergence is a term used to describe regions of the genome that do not align between two species that are being compared. The gap divergence is 13.3% between human and chimp.12 So, together, 13.3% + 1.6% = 14.9%. This means that humans and chimps share about 85.1% of their genomes…not 98.8%!13

This number reflects comparisons between the autosomes—chromosomes 1-22 in humans. What about X and Y chromosomes? The researchers published a previous paper in Nature in May of 2024 that looked specifically at sex chromosomes.14 While the X chromosome aligns at about 97.6-98% of the positions, like the autosomes, the Y chromosome alignment drops off. When researchers try to align the human Y chromosome to the chimp, the pair-wise alignment is 45%, but the number drops to 26.2% when aligning chimp to the human genome.15

Over the last several years, other researchers have tried to examine this question using the data available in public DNA sequence databases. For instance, Jeff Tomkins, who worked on the chimp genome assembly years ago, ran analyses on human/chimp similarity. Based upon analyzing a series of segments of DNA and comparing them, Tomkins found ~70-88% of DNA matches between human and chimp genomes depending on the specific analysis tools used.16 Tomkins works with the Institute for Creation Research and his calculations and papers appear to have been largely ignored by the mainstream research community. This is another example of secular research findings that are consistent with conclusions previously reached by Creation science researchers.

A geneticist from the UK also examined this question in 2018. Using comparisons from available genetic data, Dr. Richard Buggs concluded: “The percentage of nucleotides in the human genome that had one-to-one exact matches in the chimpanzee genome was 82.34%.”17 He has followed up these recent calculations and suggested that these new similarity numbers seem to match his results from 2018.18

We are also beginning to see science news outlets, such as Live Science, which are acknowledging that the new comparisons do not line up with the 98% similar value: “Sections of human DNA without a clear counterpart in chimp DNA make up approximately 15% to 20% of the genome, Marques-Bonet said. For example, some bits of DNA are present in one species but missing in the other; these are known as ‘insertions and deletions.’”19 Later in the Live Science article, this statement is found: “In fact, a 2025 study found that human and chimpanzee genomes are approximately 15% different when compared directly and completely.”20

Objections Raised

There are defenders of evolution that object to the new similarity number because the gap divergence may be overstating the differences. Some of the gap divergence is in repetitive DNA elements and represents differences in the number of repeats. Repetitive DNA sequences are regions where the same string of nucleotides is repeated over and over. This repeated string may be short (as in 5-10 nucleotides) or may be much longer. Previously, much of this repetitive DNA was thought to be junk left over from the long history of evolution in our genomes. However, new research in the last 15 years has shown that these sequences often have functional consequences when they are altered or removed or expanded.21 This objection appears to assume differences in repetitive elements are trivial. From a design perspective, we would predict those differences to be meaningful, and the research appears to be confirming this truth.22 In fact, a design perspective would predict that these repetitive elements are important and functionally relevant. The research continues to support that perspective!

What Are Some Key Takeaways from This Research?

First, it is clear that humans and chimps do not share 98.8% of their DNA when the full genomes are compared. The number appears to be closer to 85% for the autosomes. Second, the Y chromosome is strikingly different between humans and chimps, and this difference is not typically captured in the overall similarity numbers. Third, the key areas of difference include several areas where repetitive elements are found. This implies that these repetitive regions are not the leftover junk of evolution but likely represent very important functional regions. From a design perspective, we predict that these regions will provide much fruitful exploration going forward for researchers exploring human/chimp differences. Finally, it should be noted that genetic similarity between organisms can be explained both in a design model and a common ancestry model. In other words, common ancestry is not a necessary explanation for similarity. Organisms designed to live in the same environments, digest the same carbon-based biomolecules, power the same kinds of muscles and body movements, and have similar body and bone structures should be expected to have similar DNA sequences. This should not surprise us.

Conclusion

When examined from end to end, the latest evidence indicates that the genomes of humans and chimps are about 15% different. The 1-2% difference is just a myth that needs to be tossed in the “dust bin of history.” In terms of understanding the 85% similarity from a design perspective, it is reasonable for the Designer to have reused genetic code across different organisms–especially given the overall similarities. Interestingly, this reuse of similar genetic elements has accelerated our research and discovery of new information in genetics and molecular biology. In the wisdom of the Creator, He made the creation a place that could be explored and coherently understood. And in doing so, He left evidence of “His divine power and nature” (Romans 1:20).

Endnotes

1 E.S. Lander, et al., Consortium International Human Genome Sequencing (2001), “Initial Sequencing and Analysis of the Human Genome,” Nature, 409[6822]:860-921.

2 B.E. Bernstein, et al. (2012), “An Integrated Encyclopedia of DNA Elements in the Human Genome,” Nature, 489[7414]:57-74.

3 Robert H. Waterson, Eric S. Lander, and Richard K. Wilson (2005), “Initial Sequence of the Chimpanzee Genome and Comparison with the Human Genome,” Nature, 437[7055]:69-87; Human Genome Project Timeline (2022), https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project/timeline.

4 Waterson, et al. (2005).

5 R. Carter (2025), “Why I Am Not Bothered by Human-Chimp Similarity,” https://creation.com/human-chimp-similarity-explained.

6 Waterson, et al. (2005); D. Yoo, et al. (2025), “Complete Sequencing of Ape Genomes,” Nature, 641[8062]:401-418.

7 J.P. Tomkins (2011), “How Genomes Are Sequenced and Why It Matters: Implications in Comparative Genomics of Humans and Chimpanzees,” Answers Research Journal, 4:81-88.

8 Yoo, et al. (2025).

9 Yoo, et al. (2025).

10 Sergey Nurk, et al. (2022), “The Complete Sequence of a Human Genome,” Science, 376[6588]:44-53.

11 Yoo, et al. (2025), see the Supplementary Figure III.12.

12 Yoo, et al. (2025). see the Supplementary Figure III.11.

13 It should be noted that this number varies based upon whether you are comparing human to chimp or chimp to human, but both values end up in this same range.

14 Kateryna D. Makova, et al. (2024), “The Complete Sequence and Comparative Analysis of Ape Sex Chromosomes,” Nature, 630[8016]:401-411.

15 Makova, et al. (2024).

16 J. P. Tomkins (2011), “Genome-Wide DNA Alignment Similarity (Identity) for 40,000 Chimpanzee DNA Sequences Queried against the Human Genome Is 86-89%,” Answers Research Journal, 4:233-234; J.P. Tomkins (2013), “Comprehensive Analysis of Chimpanzee and Human Chromosomes Reveals Average DNA Similarity of 70%,” Answers Research Journal, 6:63-69.

17 R. Buggs (2018), “How Similar Are Human and Chimpanzee Genomes?,” https://richardbuggs.com/2018/07/14/how-similar-are-human-and-chimpanzee-genomes/.

18 R. Buggs (2025), “More on Human-chimp Genomic Similarity,” https://richardbuggs.com/2025/09/08/more-on-human-chimp-genomic-similarity/.

19 C. Brincat (2025), “Do Humans and Chimps Really Share Nearly 99% of Their DNA?,” Live Science, https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/human-evolution/do-humans-and-chimps-really-share-nearly-99-percent-of-their-dna.

20 Ibid.

21 Jeffrey Snowbarger, Praveen Koganti, and Charles Spruck (2024), “Evolution of Repetitive Elements, Their Roles in Homeostasis and Human Disease, and Potential Therapeutic Applications,” Biomolecules, 14[10]:1250; Heather A. Lawson, Yonghao Liang, and Ting Wang (2023), “Transposable Elements in Mammalian Chromatin Organization,” Nature Reviews Genetics, 24[10]:712-723.

22 Casey Luskin (2024), “From the ‘Junk DNA’ Files: Can ‘Degraded’ Line Elements Still Be Functional?,” https://scienceandculture.com/2024/05/from-the-junk-dna-files-can-degraded-line-elements-still-be-functional/.

REPRODUCTION & DISCLAIMERS: We are happy to grant permission for this article to be reproduced in part or in its entirety, as long as our stipulations are observed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home