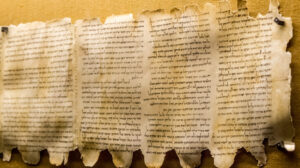

Could New Dead Sea Scrolls Research Help to Confirm the Reliability of the Bible?

Could New Dead Sea Scrolls Research Help to Confirm the Reliability of the Bible?

A fascinating new peer-reviewed journal article, recently published in the open access journal PLoS One, presents data that may challenge the long-held scholarly consensus that the book of Daniel reached its final form between 167 and 164 B.C.1 The problem with this consensus, as I have attempted to show,2 is that the book of Daniel represents itself as a product of the sixth century. Simply put, one has a hard time harmonizing the critical scholarly theory of Daniel’s date with a firm belief in the Bible’s reliability. Most critical scholars simply jettison the book of Daniel as a reliable source, treating its main characters as legendary. For example, a leading critical scholar in the field states, “According to the consensus of modern critical scholarship, the stories about Daniel and his friends are legendary in character, and the hero himself most probably never existed.”3 This consensus has gone unthreatened among liberal scholars for more than a century.

Regarding the critical dating of the book of Daniel, even the discoveries of the Dead Sea Scrolls did not seem to challenge the consensus. For example, Frank Moore Cross, a longtime professor at Harvard University and one of the first experts on the Dead Sea Scrolls, dated the oldest of the Daniel manuscripts (4QDanc) to “the late second century,” “no more than about a half century younger than the autograph.”4 This is a remarkable claim since we have no other manuscript of the Bible so close to a book’s date of composition. Cross reached his date on paleographic grounds. (Paleography is a science that attempts to date manuscripts based on the style of handwriting.)

Scholars who followed Cross’s paleographic dating were not quite as confident about the date of the manuscript. A leading Scrolls scholar, Eugene Ulrich, dates 4QDanc to the late second or early first century.5 This offers a little more wiggle room between the liberal scholarly reckoning of the book’s composition in the 160s B.C. However, newly published research forces a reevaluation of the paleographic dating of the Scrolls in general, and of 4QDanc in particular.

How Has the Critical Consensus Been Challenged?

A team of researchers led by world-renowned Scrolls expert Mladen Papović combines new methods of Carbon-14 dating with Artificial Intelligence programming to redate a number of Scrolls. Since the Dead Sea Scrolls corpus consists of more than 900 manuscripts, further research must be done to draw conclusions more broadly, but the current results seem promising. Using new developments in technology, the Carbon-14 dating method was employed to reevaluate the standard theories about ancient Semitic paleography.

The Artificial Intelligence model, termed “Enoch,” utilizes “Bayesian ridge regression” to predict the dates of manuscripts based on “binarized” images of the scrolls. The Enoch Model’s paleographic analysis validates the Carbon-14 dating in more than 85% of cases. This result was deemed good enough to apply to 135 other Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts whose dates are in doubt. The work of the Enoch Model was checked against the sentiments of human experts in ancient Hebrew and Aramaic paleography, and the human experts deemed 79% of its predictions to be reliable. In other words, the researchers attempt to bring together old and trusted methods with exciting new leaps forward in technology to triple-check the credibility of scholarly claims.

The practical takeaway from this study is that some of the Scrolls are much older than previously thought. First, the new Carbon-14 dating tests and AI paleographic analysis allow us to push back the date of some manuscripts by 50 years or more. This news is significant on its own. But the study also demonstrates that the Hebrew and Aramaic scripts used in the period, typically termed the “Hasmonean” and “Herodian” scripts, respectively, are older than previously thought. Scholars have long believed that these scripts were in transition around the mid-first century B.C. In other words, previous paleographers have been inclined to date a manuscript with the “Herodian” script to the late first century B.C. at the earliest, while the “Hasmonean” script manuscripts could be dated earlier. The new research suggests that the two scripts actually coexisted from a much earlier period, making previous paleographic theories about the Dead Sea Scrolls unreliable.

How Does This Apply to Daniel?

One of the sample manuscripts analyzed is the oldest known copy of the book of Daniel. As we have previously mentioned, Cross (and those who follow him) have comfortably dated this manuscript, on paleographic grounds, to the late second century B.C. Ulrich might push this date even further forward, to the first half of the first century B.C. These dates allow the original composition of the book of Daniel to fall in the 160s, as liberal scholars have traditionally maintained. However, Popović and his collaborators conclude their reanalysis of the Carbon-14 and paleographic evidence as follows: “Sample 4Q114 [i.e., 4QDanc] is one of the most significant findings of the 14C results. The manuscript preserves Daniel 8-11, which scholars date on literary-historical grounds to the 160s BCE. The accepted 2σ calibrated range for 4Q114, 230-160 BCE, overlaps with the period in which the final part of the biblical book of Daniel was presumably authored.”6

This statement is hard to believe. The authors do not wish to dismiss the scholarly consensus, so they suggest that 4QDanc dates to the book’s exact time of composition. In other words, they do not claim that the manuscript is an original copy of Daniel, but certainly contemporary with the original copies. To put it mildly, this claim is unlikely to be true. Still, the researchers allow the manuscript to be authored in “the 160s BCE,” which is decades older than Cross and Ulrich previously thought. This alone is significant.

Moreover, we should note that the authors bias the interpretation of their evidence. Since liberal scholars require the book of Daniel to have reached its final form in the 160s, any potential date earlier than that threatens to upend the consensus. The dates “230-160 BCE” are obviously broader than most scholars would call “the period in which the final part of the biblical book of Daniel was presumably authored.” I understand that these date ranges are intended to account for a margin of error, but they include what scholars usually call the terminus post quem (“the date after which”) and the terminus ante quem (“the date before which”), respectively. While Popović and his collaborators are cautious to allow room for the scholarly consensus, their data suggest the possibility that the consensus date of Daniel is objectively wrong.

Scholars believe that the book of Daniel had to be composed prior to 164 B.C. because it does not clearly mention the death of the anti-Jewish tyrant Antiochus IV Epiphanes. However, the book does mention atrocities committed during his reign, specifically ones dating during the years 167-164 B.C. Daniel chapters 8-11 refer to Antiochus as the “little horn” (8:9), and mention with great specificity the events of his reign, such as interrupting Temple sacrifice (8:11-12), his war with the Ptolemies (11:20-35), and his exaltation of himself as a god (11:36-45). These incredibly detailed passages match precisely the historical realities as documented in the books of 1-2 Maccabees and in Greek historians such as Polybius. Yet, Antiochus’s death is only obliquely referred to (11:45). Thus, the critical assumption emerges that the book was composed during the reign of, but prior to the death of, Antiochus IV.

To be clear, one of the primary reasons liberal scholars deny the book of Daniel a sixth-century date is that they assume it is impossible for the biblical authors to know the future with precision. Predictive prophecies like those found in Daniel 8-11 must be regarded, as the German critic Otto Eissfeldt once called them, vaticinia ex eventu, or “prophecies after the event.”7 In other words, the so-called “prophecies” of Daniel are really no prophecies at all, but historical reflections on events that occurred in recent memory. This is the scholarly consensus. If Popović and his collaborators are correct, the new dates assigned to the oldest manuscript of Daniel might force a change in how scholars date the book of Daniel.

Conclusion

The historical accuracy of the book of Daniel regarding the anti-Jewish persecutions of Antiochus IV is virtually uncontested. Critical scholars usually explain this accuracy by simply arguing that the authorwas not a prophet of the sixth century, but an eyewitness to the events of the 160s B.C. The possibility that a manuscript of the book (4QDanc) could be older than the events it records forces a reevaluation of the predictive power of Scripture. Whether Daniel was composed in circa 530 B.C. (as Bible believers traditionally maintain) or in circa 230 B.C. (the oldest possible date of 4QDanc) is irrelevant. Any date prior to the reign of Antiochus IV not only means the critical consensus is wrong, but also that the predictive prophecy of Scripture is right.

Endnotes

1 Popović Mladen, Maruf A. Dhali, Lambert Schomaker, Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Jacopo La Nasa, Ilaria Degano, Maria Perla Colombini, and Eibert Tigchelaar (2025), “Dating Ancient Manuscripts Using Radiocarbon and AI-based Writing Style Analysis,” PLoS One 20[6], e0323185, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323185.

2 Justin Rogers (2016), “The Date of Daniel: Does It Matter?” Reason & Revelation, 36[12]:134-137,141-143, December.

3 John J. Collins (1993), Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel in Hermeneia Old Testament Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress), p. 1.

4 Frank Moore Cross (1961), The Ancient Library of Qumran (Garden City, NY: Doubleday), p. 43.

5 Eugene Ulrich (2001), “The Text of Daniel From Qumran,” in The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception, ed. John J. Collins and Peter W. Flint (Leiden: Brill), 2:574.

6 Popović, et al., 20[6]:3.

7 Otto Eissfeldt (1965), The Old Testament: An Introduction, trans. Peter R. Ackroyd (New York: Harper and Row), p. 517.

REPRODUCTION & DISCLAIMERS: We are happy to grant permission for this article to be reproduced in part or in its entirety, as long as our stipulations are observed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home