What is Rabbinic Judaism?

What is Rabbinic Judaism?

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The following article was written by A.P. auxiliary writer Dr. Justin Rogers (Ph.D., Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion). Dr. Rogers is Dean of the College of Biblical Studies and Professor of Bible and Judaic Studies at Freed-Hardeman University.]

Most American Christians are undereducated on the beliefs and practices of their religious neighbors. As the American religious landscape becomes increasingly diverse, it is wise for Christians to learn about the groups that surround them. A basic understanding of the world religions makes us more sensitive to the beliefs and practices of our neighbors and equips us to reach others with our faith and to defend the Truth “with gentleness and respect.”1 We will attempt to survey in this article the foundations of one world religion, the smallest of the so-called “three major world religions,” Judaism.

Modern Judaism is only partially based on what Christians call the Old Testament.2 Personal piety came to replace sacrifice in Judaism long ago, in texts like Midrash Leviticus Rabba, which suggests a life of spiritual sacrifice is just as efficacious as a blood offering. Therefore, asking why Jews today do not sacrifice is evidence of an unawareness of their beliefs and practices. Like Christians, Jews recognize the authority of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, but they also recognize the validity of later traditions and texts. Just as modern Catholicism draws on centuries of traditions that Catholics affirm as authoritative, so also modern Judaism draws on traditions passed down through the centuries through the rabbis. Therefore, like Catholicism, one may legitimately speak of Scripture and Tradition as the twin pillars of modern Judaism. (It is not without significance that Geza Vermes titled his 1961 work on Jewish interpretation Scripture and Tradition in Judaism.)

Who Are the Rabbis?

The term “rabbi” means “one greater than I” and was an honorific way of referring to one’s teacher. As far as our current state of knowledge is concerned, the term dates back no further than the first century A.D., and the New Testament is the earliest text to use it. Most scholars believe the rabbis are the successors of the Pharisees, the most popular Jewish group of the New Testament era. The rabbinic literature never uses the term “Pharisee,” but there are several reasons for regarding them as the predecessors of the rabbis. First, ancient sources refer to figures such as Gamaliel and his son Simon as Pharisees, and both are claimed by the later rabbis (cf. Acts 5:34; Josephus3). Second, the Pharisaic movement was always carried by popular support, especially in Judea, whereas the two other main Jewish parties—the Sadducees and the Essenes—were either closely connected with the Temple (Sadducees) or were sectarian in nature (Essenes).4 Therefore, neither of the other two main Jewish sects had a major influence on the populace as a whole.

The main reason for connecting the Pharisees and the rabbis is that both groups considered their distinctive tradition authoritative.5 Jesus tends to agree with the Pharisees on most matters (e.g., Matthew 23:2-3) but criticizes their insistence on the authority of non-biblical tradition (e.g., Matthew 15:3; Mark 7:9). Since their tradition serves to exalt the authority of the Pharisees and the later rabbis, it is appropriate to discuss the concept in more detail.

The Rabbinic Tradition

By design, the rabbinic tradition was to be transmitted orally, not to be written. The earliest rabbis, whose opinions are recorded in the Mishna, are called the Tanna’im, or “repeaters” of the oral tradition. The rule of repetition, rather than writing, remained in effect until Rabbi Judah “the Prince” codified the Mishna in ca. A.D. 200, the first written source of Rabbinic Judaism. A rabbinic document known as Midrash Tanhuma6 questions why God initially speaks “all” the words of His law (Exodus 20:1), and then later commands Moses to “write” them down (Exodus 34:27). The rabbis explain that God initially wanted the entire Law to be delivered orally, but after Moses expressed the desire to write it down, God condescended as follows:7 “Give them the Scriptures in written form, but deliver the Mishna, the Aggada, and the Talmud orally.”8 This later Midrash expands on a common rabbinic theme, namely, that their teaching was to imitate God’s revelation at Sinai. They were to copy and read the written Law, and they were to memorize and repeat the oral law.9

The decision to write down the oral law was, therefore, seemingly a contradiction of the rabbis’ own policy. The rabbinic literature never works out the contradiction, but a number of modern scholars have offered suggestions.10 Perhaps it was simply a practical matter. One can imagine that the oral tradition eventually became too large to memorize, and different rabbis remembered different teachings in contradictory form. Therefore, writing was an attempt to standardize the rabbinic tradition, getting everyone “on the same page,” so to speak. It is also possible that the written form of the oral tradition was intended for private study to facilitate the rabbinic education. Modern scholars have analyzed the rhetoric of the Mishna in particular, finding that it is written to facilitate memorization. Ultimately, modern readers of the rabbinic literature are forced to live with a paradox: our only access to the oral law is in its written form.

Why Does the Oral Tradition Exist?

The rabbis’ own summary of the rabbinic tradition is found at the beginning of the Mishnaic tractate Pirke Avot: “be patient in judgment, raise up many students, and build a fence around the Law” of Moses (1:1). The most programmatic of these commandments is the last. One of the primary aims of the rabbinic experiment was to protect the written law from being violated. The oral law was always viewed as a compliment, not a competitor, of the written Law of Moses. Some sources feature the oral law as a distinct set of traditions preserved independently,11 while others speak of the oral law as a set of authorized interpretations of the Mosaic Law and thus dependent on it.12 The latter presentation is the one that seems more plausible historically.

The rabbinic traditions were well-intended to keep people from violating biblical law. Inventing the notion of an oral law served two related purposes. First, it helped to define what the 613 biblical laws in the Pentateuch actually meant. For example, the Law of Moses instructs the Israelites to do no work on the Sabbath (Leviticus 23:3) but gives few examples of what types of work violate the Law (Numbers 15:32-36 is a rare exception). By contrast, the Mishna—the first written version of the oral law—records some 39 categories of work forbidden on the Sabbath, unpacking each in extreme detail. If one were to observe the teachings of the rabbis, he could rest assured that he had kept the Law.

Second, claiming that the oral law is traceable to Moses on Sinai serves to authorize the rabbis as tradents of the tradition, and thus as the most qualified interpreters of the Bible. In the marketplace of competing biblical interpretations, the claim to possess a stream of exceptional divine revelation would have helped the rabbis to assert their authority. The claim also ensured that no single rabbi possessed an authority of his own, for the rabbis studiously place themselves within an authorized tradition. The contribution of every esteemed sage lies in his ability to transmit accurately what he has received, not to add anything new.

What Is the Mishna?

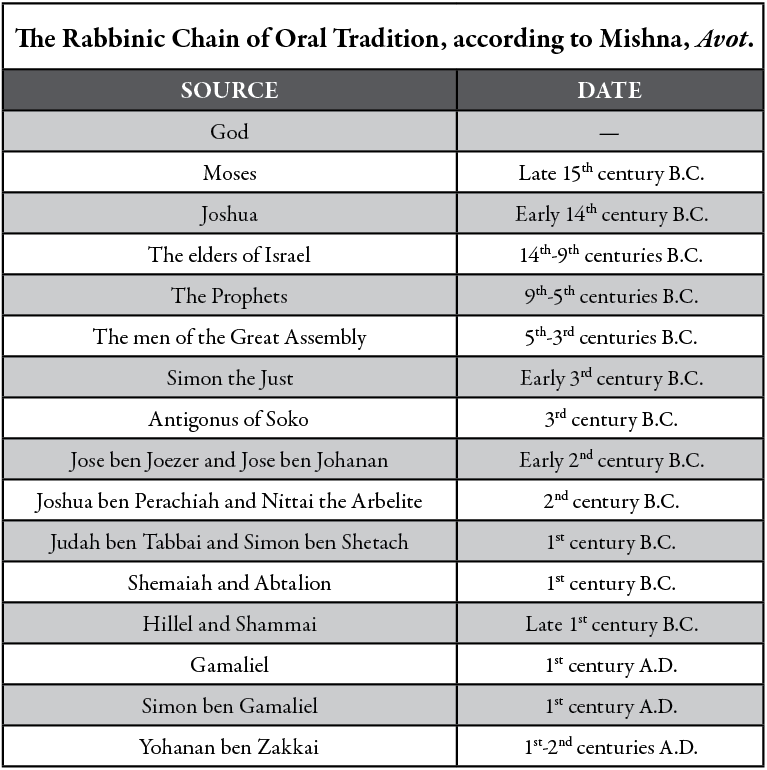

The Mishna is the first written source of Rabbinic Judaism. In this document, we have a mythical account of the origins of the Jewish oral tradition.13 We are told that, on Mount Sinai, God revealed two laws to Moses, one to be written (the Pentateuch) and the other to be passed down orally. Moses shared this oral law with Joshua, Joshua with the elders of Israel, the elders of Israel with the biblical Prophets, and the biblical Prophets with “the men of the great assembly.” From here, the oral tradition was passed on to and through various individual sages down to the time of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, who, following the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70, became the founder of the movement known to us in the rabbinic literature.

The Mishna is divided into six divisions, known in English as “orders:” (1) Zeraim (“Seeds”) on agriculture; (2) Moed (“festival”) on holidays; (3) Nashim (“women”) on regulations pertaining to the family; (4) Nezikin (“damages”) on cases and procedures in the Jewish court system; (5) Kodashim (“holy things”) on sacrificial procedures; and (6) Tahorot (“purities”) on ritual purity. These are the categorical groupings that encompass all of the laws governing Jewish life.

What Is the Talmud?

The Talmud, known as the Bavli, or Babylonian Talmud, is a commentary of sorts on the Mishna. The word Talmud is an Aramaic word meaning “teaching.”14 It includes much of the Mishna along with what is called the gemara, or “complete teaching.” Actually, the Talmud does not cover all of the Mishna. Only 36.5 of the Mishna’s 63 tractates, comprising only four of its six “orders,” receive comment.15 It is unclear why much of the content is omitted, but the traditional explanation is that some of the Mishna’s Palestinian agricultural concerns were irrelevant to the Babylonian context of the Talmud.

The Talmud was compiled around A.D. 500 and was an effort to impose the rabbinic rules of the land of Israel on the Babylonian Jewish community. There is another Talmud, known as the “Jerusalem Talmud,” compiled in the land of Israel about A.D. 400, but it has not been considered worthy of the same status as the Babylonian Talmud. The same is true of another collection of rabbinic tradition hailing from the land of Israel, the Tosefta (compiled ca. A.D. 300). Since traditional Jews regard the collection represented by the Babylonian Talmud to be inclusive of the earlier rabbinic tradition (at least, theoretically), when the word “Talmud” is used, it is usually only the Bavli that is intended.

The Talmud contains much material that is attributed to the rabbinic oral tradition but unrecorded in the Mishna, the Tosefta, or the Jerusalem Talmud. Two categories of content describe the non-Mishnaic material that is not necessarily paralleled in the earlier collections.16 First, we have what is called beraitot (or, in the singular, beraita’), which means “external content.” This material is “external” to the Mishna, but is nevertheless attributed to the tanna’im, or the sages of the Mishnaic period. Second, we have the teachings of the sages belonging to the generation after the Mishna. The rabbis of this era, who flourished in the third and fourth centuries A.D., are known as the ’amChiralityora’im, or “sayers.”

The Talmud is a monumental accomplishment, representing more than two million words of content and taking up an entire bookshelf in the standard editions. The Talmud is nearly five times longer than the entire Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, and is considered the authoritative expression of Jewish faith, though other rabbinic collections are also considered important for the tradition. For example, Jews traditionally treat the rabbinic commentaries, or Midrashim, with respect and mine them for encouraging material. Nevertheless, the Talmud remains the foundational text of Modern Judaism. As Talmud scholar Stephen Wald describes it,

The Talmud Bavli represents the growing literary achievement of this entire period of Jewish history—which is in fact often simply referred to as the “talmudic period.” It was ultimately accepted as the uniquely authoritative canonical work of post-biblical Jewish religion, providing the foundation for all subsequent developments in the fields of halakhah [Jewish law] and aggadah [Jewish theology]…. Despite manifest difficulties of language and content, the study of the Bavli has also achieved an unparalleled place in the popular religious culture of the Jewish people.17

Conclusion

Modern Judaism is founded on rabbinic Judaism, which most likely has its roots in the Pharisaic movement of the first centuries A.D. The rabbis’ foundational concept was the assertion that two laws were given on Sinai, one written and the other oral. The oral law was passed down from one generation of sages to the next so that the latest tradents of the tradition could be considered authoritative in their teaching. Therefore, if one accepted the oral tradition of the rabbis, one had to view with suspicion the teachings of all others. While the Pharisees apparently did not have as developed a notion of the oral tradition and its transmission, they nevertheless considered their traditions authoritative.

Eventually, the oral teachings of the rabbis were committed to writing, first in the Mishna (ca. A.D. 200), then in author writings of the so-called Tannaitic period. Finally, the Babylonian Talmud (ca. A.D. 500) became the greatest expression of authorized rabbinic teaching, incorporating the Mishna and many other traditions both from the Tannaitic and the Amoraic periods. It would be the Babylonian Talmud that Jews in the Middle Ages took as the final and fullest expression of their faith, and the text that continues to be shared with generations of Jews, both those training for the rabbinate and those seeking to grow closer to the God of the covenant. If Christians hope to reach their Jewish friends with the Gospel, it is helpful to know something about their history, tradition, and literature.18

Endnotes

1 1 Peter 3:15, ESV.

2 Jewish people refer variously to the Scriptures (the “Protestant” Christian Old Testament) as the Bible, the TaNaK (an acronym for the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings—the Torah, the Nevi’im, and the Kethuvim), or Mikra (“what is written”).

3 Flavius Josephus (1987 reprint), The Life of Flavius Josephus in The Works of Josephus, trans. William Whiston (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson), 190-196.

4 On the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes as the three main Jewish groups, along with their characteristic teachings, see Josephus, Jewish War, 2:119-166; Antiquities, 13:171-173.

5 For the Pharisees, e.g., Mark 7:1-13; Josephus, Antiquities 13.297, 408; for the rabbis, e.g., Mishna, Avot 1-2.

6 Published by Solomon Buber.

7 All translations of ancient languages are mine unless otherwise noted.

8 Ki Tisa 17.

9 Cf. Jerusalem Talmud, Megilla 4:1.

10 See Elizabeth Shanks Alexander (2007), “The Orality of Rabbinic Writing,” The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature, ed. Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert and Martin S. Jaffee (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 38-57.

11 E.g., Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 54b.

12 E.g., Babylonian Talmud, Menahot 29b.

13 Avot 1-2.

14 The Mishna is written in Hebrew, but the Babylonian Talmud (when it does not quote the Mishna) is written in Aramaic. Therefore, the rabbis who compiled the Talmud were bilingual.

15 The Talmud excludes all of Zeraim with the exception of the tractate Berakot and all of Tahorot with the exception of the tractate Niddah.

16 On the complex relationship between the Babylonian Talmud and earlier rabbinic material, see H.L. Strack and Günter Stemberger (1992), Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, trans. and ed. Markus Bockmuehl (Philadelphia: Fortress), pp. 197-201.

17 Stephen Wald (2007), “Talmud, Bavli,” in The Encyclopedia Judaica, ed. Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum (San Francisco/Jerusalem: MacMillan/Keter), second edition, 19:470.

18 To learn more, the Sefaria website and mobile application are excellent (sefaria.org).

REPRODUCTION & DISCLAIMERS: We are happy to grant permission for this article to be reproduced in part or in its entirety, as long as our stipulations are observed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home